As the election draws near, we are once again forced to pretend that there is any justice in the system of mass democracy. Everyone knows, in their hearts, that it is a sham. Everyone recognizes how ridiculous it is, that the direction of our country hinges on the “undecided voter”, and yet you are emphatically encouraged to vote. Vote, vote, vote. Never is anyone given an explanation as to why they should vote, we are simply told that if we don’t vote then we will somehow end up in 1984 or the Handmaids Tale or the Hunger Games some other book for teenagers. As voting has become more widespread, politicians have adapted to attract every demographic of voter. The reading level and length of presidential speeches has declined heavily over the past century as political engagement became more accessible.

But before I start bashing democracy, let’s discuss some positive elements of Democracy. I would argue that, contrary to what people might imagine, Europeans (and the Indo-European cultures in general) are particularly democratic. They were not engaged in what we would call “liberal democracy” or “egalitarian democracy” however, they were engaged in stepped democracy. Everyone within the tribal or political unit had a voice by virtue of being a free man. They paid taxes, they responded to calls of arms, and in this small social unit even a single person can be considered an important part of the community just by existing and doing work. However, in these sort of democratic systems there is unequal power granted to respected or otherwise high-status members of the group. This doesn’t even require some sort of formal statute. When there is direct democracy in small groups, it is just sort of recognized intuitively. Also, women weren’t allowed to vote generally, because women don’t typically own land or run households, and can already influence the decisions of their husbands. We will get into 19A later, but many groups were neglected the vote because they were recognized as having unreliable or ulterior motives.

In these environments, the vote is not a right but a privilege, a concession to people who (by virtue of the small size of the group) are crucial in its continued existence. Particularly in these states, the military was often reliant on large numbers of citizen soldiers. The Greek Phalanx, for instance, was a numbers game. This is in contrast both to the Bronze and Iron Age near east and to medieval Europe, who had specialized class of highly mobile warriors who were very important for military success. In England, where the peasant longbowmen humiliated the French cavalry at Crécy, democratic engines once again began to arise, and among the Pikemen of Switzerland and Northern Italy similar things happened. The rise of the musketeer created a similar environment in the American Colonies, where there was constant conflict on the frontier with Indian tribes. This isn’t the universal cause of democracy, but it can help explain the reasoning behind democratic and liberal systems before there was ever such thing as the ideology of Liberalism. All the state really is is a protection racket, so things like “paying taxes” and “jury duty” are done from state coercion, and not from state negotiation.

However, today we live in a very different world. Wars are won through manpower, yes, but in a much more indirect way which changes the military from a voluntary organization of free men, into a technical amalgam of wage laborers, industries, and bureaucrats. Total war has not been engaged in since the end of World War II, because total war would dissolve entirely into a nuke-hurling contest which nobody wants. Not only are political bodies so large that the individual person is a drop in the ocean, but they also have no particular reason to play this negotiation game with the masses. However, the political elite got its power from democratic systems, so they have an incentive to defend these systems through abstract principals like “the right to vote”. The first defense of Democracy is usually the idea that people vote rationally for their interests, that voters have agency over their political opinions. There is plenty of evidence, however, that the masses are not merely uneducated but largely incapable of this sort of political agency. Especially in such a large and complex society with so much random variables, people are not capable of telling at first glance what problems are mass problems and if their problems are indicative of mass problems, let alone what causes these mass problems. There are two easy ways to demonstrate the inability of the masses to have political agency, which the long time HBD personality

demonstrates in this video, as well as in his essay. He estimates that anywhere from 70-95% of the American population lacks political agency based on two standards: reading comprehension and mathematical comprehension (both necessary for understanding the causes and effects of political activity). The average American reads at a middle school reading level, studies are not entirely consistent on which grade exactly but it tends to range from 6th-to-8th grade. Only around 60% of American adults can reliably analyze a passage of prose, even relatively basic prose. With more advanced prose it dwindles to around 13%. and although reading comprehension can certainly be improved with regular reading (especially from a young age) there is a large and difficult to ignore cognitive element of it. More intelligent people not only have a much higher ceiling for their reading comprehension, but also have to put in much less effort or focus in to reach it. Only 16% of Americans reliably answered this question:Only 11% of Americans could write a short paragraph about this graph, summarizing the extent to which parents and teachers agreed or disagreed on the statements about issues pertaining to parental involvement at their school.

The correct answer is anything vaguely along the lines of “Parents are generally more likely than teachers to be unsatisfied with the degree of parental involvement in schools”. It doesn’t have to be terribly specific. This example is particularly telling because it isn’t really a “book smart” thing, it’s a “how do people who get this wrong spend their whole day reading Excel spreadsheets” sort of thing.

So, Americans can’t read. Books, graphs, you name it. They’re gonna be struggling. This isn’t entirely an artefact of racial differences, this is true among White people as well. This stuff is from the 1990s, by the way, when America was about 30% Whiter. Before differences in racial makeup really had that sizeable of an effect on any sort of nationally sourced cognitive scores. Obviously the differences are exaggerated in groups with average IQs below 100, and they are mitigated ingroups with average IQs above 100 (my guess: ancient Athens fit this bill). This poses a serious problem: People don’t have a way of reliably parsing important facts relevant to policymaking from things they read, and if they can’t get it from things they read or from graphs they see shared online, they probably won’t be able to get it from listening to things either. Anyone who reads audiobooks should recognize this — I’ve tried reading audiobooks at the gym. You don’t get nearly as much information out of it. as you’re supposed to. So they all rely on certain groups to tell them what to believe about pretty much everything. Because, as I said, there isn’t a reliable way to distinguish personal issues from mass issues when you live in a country of 330 million, with one of the most complex and carefully analyzed economies in human history. I would even argue that seemingly obvious things like inflation present a difficulty because a lot of people have heavily distorted and selective memories from the past. Certain things going up in price does not necessarily mean prices are rising across the board, but when you are told by a person whose opinion you trust that inflation is rising, you are much more likely to attribute such things to inflation. Which, albeit, is completely rational. But, you’re not really making a decision on anything.

Okay, but surely people can learn to be better at reading, can’t they? Well, maybe some people, but across the board there are highly diminishing returns on these things. I’ll get into this later in the post. Public Education is basically a jobs program and a daycare with a bit of cargo-cultism mixed in, the aforementioned Bronski has some good material on that as well as the economist Bryan Kaplan. And this is where I would like to get into the math side of this… Probability is really the basis for all of science — you can’t *know* anything definitively from sensory information, but you can use prior observations to estimate what will probably happen as a result of some physical process, and accordingly what probably did happen for some observed process to occur. Because society is an observed phenomenon, it follows the same demands as the scientific method. This is why anecdotal evidence is viewed as faulty. I’ve noticed a lot of normies don’t actually know this, they think anecdotal evidence is bad because anecdotes don’t have evidence behind them. Maybe they are just bad people who do not trust their friends, but this is not the reason, and it leads to them not realizing that many political movements are based entirely on a small collection of anecdotes. BLM is the most famous example of recent memory. “George Floyd is evidence of police brutality”. You see it with the gun debates too, “this school shooting is evidence of a school shooting problem” even though the chances of getting killed in a school shooting are less likely than plenty of things we do not identify as a “problem”. As someone who grew up during the zenith of school shootings, I never really felt worried about them and even when my school experienced a lockdown that lasted at least 6 hours my main concern was “I hope I don’t have to go to the bathroom”. This is just oracular behavior, and I would consider these augurs far less prophetic than the ones trained at the college of pontiffs in ancient Rome.

So, if you can’t understand basic properties of statistics, which requires understanding basic math, you are forced to rely on the whims of statisticians who are often extremely dishonest about how they portray their information in the opening and closing sections of their studies. Even more dishonest are the journalists who, having likely only read these sections, add their own twist on the results of such studies. I see this so often in the population genetics world, that it makes me have a deep hatred of Journalists. Also, a lot of academics are actually extremely bad statisticians, and will put mathematical fluff in their papers to make them look stronger because the peer review boards are also bad at statistics. Oh yeah, calculus and linear algebra are also fundamental.

Bronski uses the example of the AP Statistics exam to demonstrate that even a large swathe of the smarter quarter of American students do terribly on this “easy” exam, which he is probably right to say (I didn’t take AP Statistics, but I took plenty of other APs), an exam on very basic statistics which the students spent a year learning. It’s true, the APs are extremely lenient on grading. You only usually have to get around three quarters of the questions correct to get the highest score, a 5, and you don’t even need to get half of the questions correct to score a passing grade.

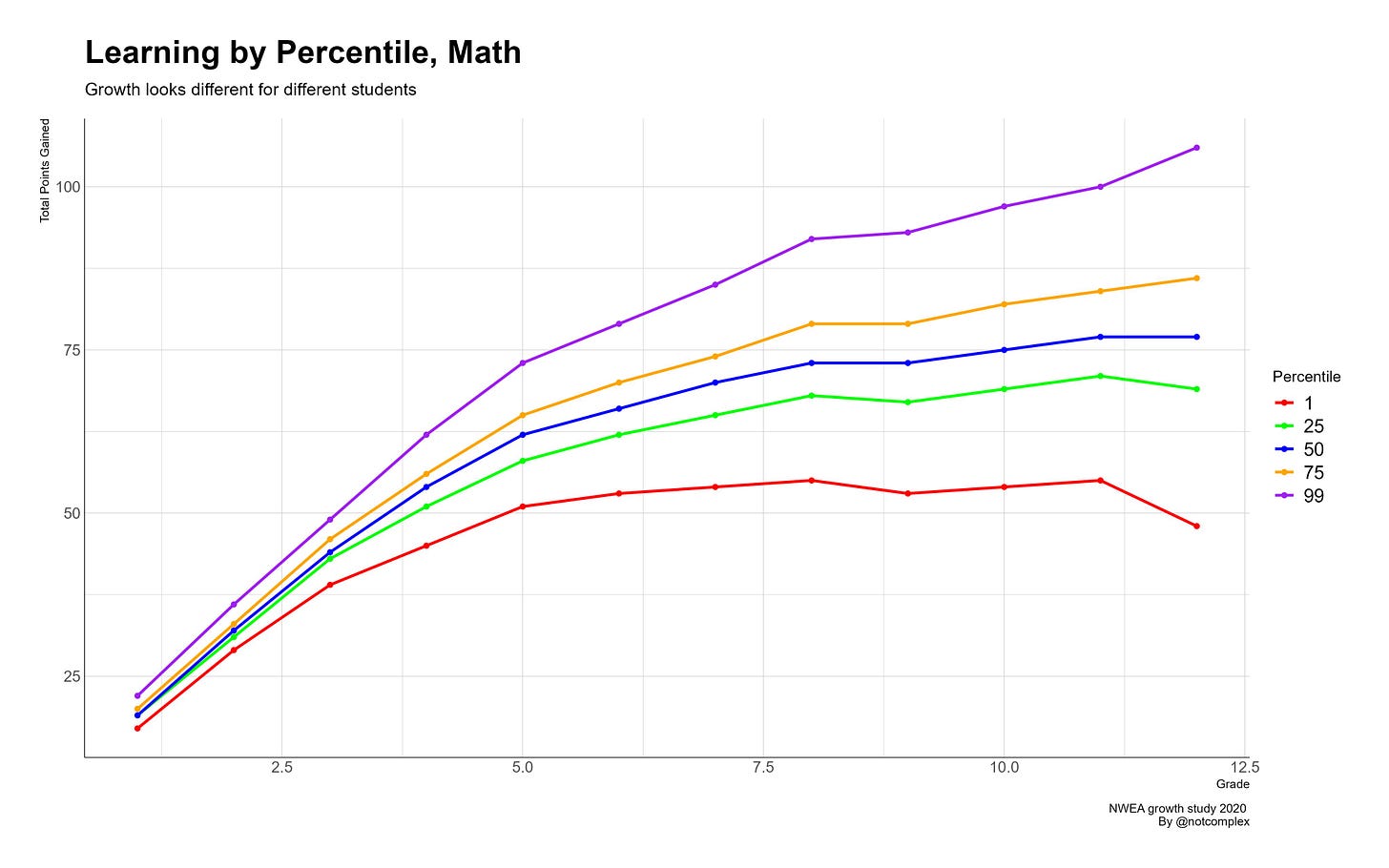

Which brings me to this graph:

Reading comprehension is a similar story:

We all know that adults forget most of the math they learn in school, but did you know that the median student gains barely any math knowledge after 8th grade? Basic algebra seems to be the intellectual limit for much of the population. Reading comprehension also taps out. I would also estimate that a decent chunk of the increases in scores going on before 8th grade in these graphs is not the product of learning but of simple biological development.

Without these two basic tools of understanding our world, most potential voters literally cannot make an educated opinion. Furthermore, many people who can make an educated opinion simply don’t want to, because politics is a terrible hobby. You usually can’t impact its outcome, it’s boring, it causes social conflict, and it can endanger your career if you talk about it a lot. And the less political agency you have, the more effort you have to put into this hobby just to maintain the ability to argue in favor of your beliefs. This is why I say, in the title, “you might as well choose leaders by lot”. Because people who are voting came to their beliefs through a sort of pinball machine of social conditions and media algorithms. They either cannot or will not spend energy analyzing an article or book about a historical event or document, they cannot read the statistical information from an academic paper correctly. I would say this makes up probably around 70-80% of the population.

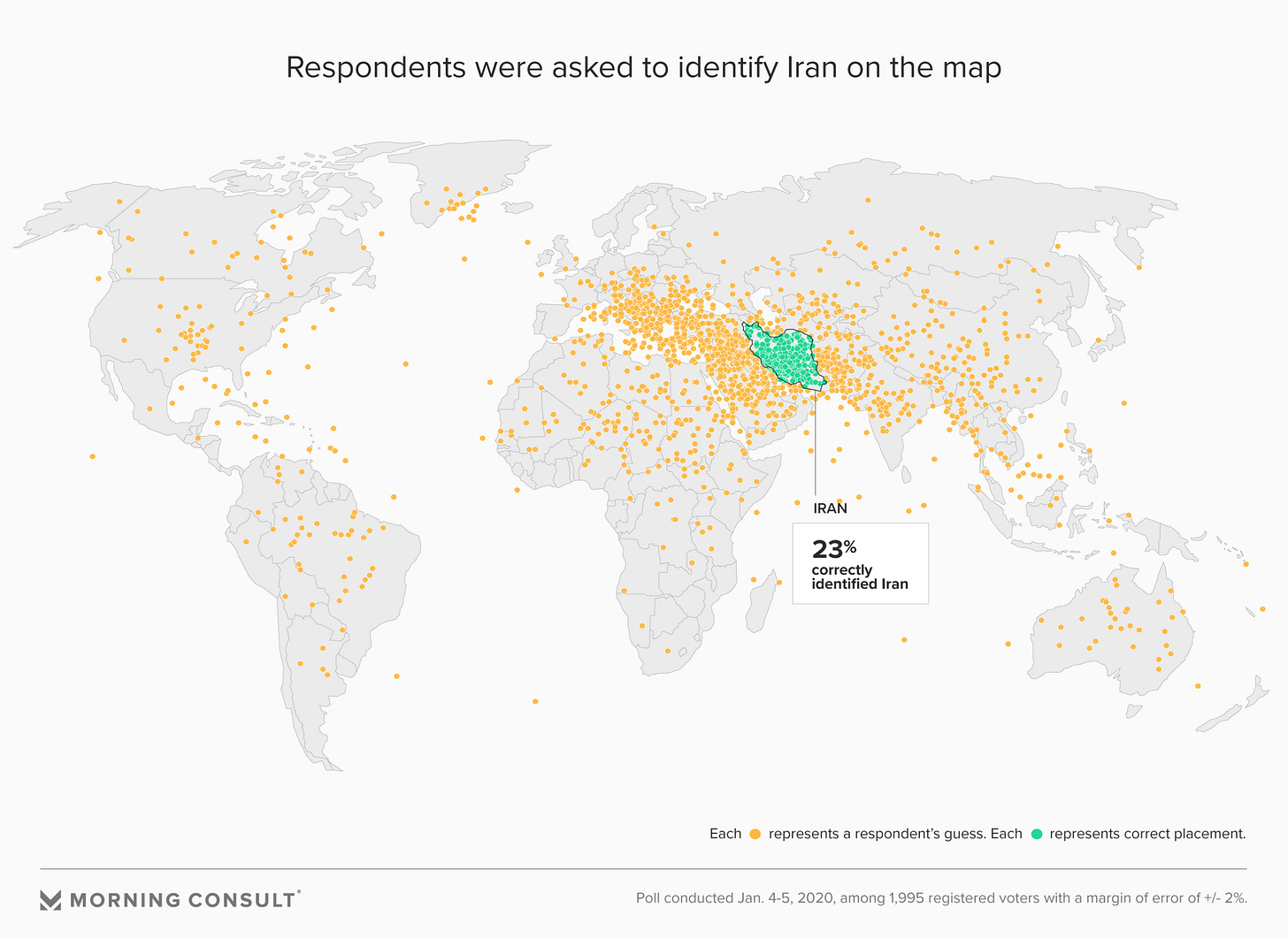

Looking at knowledge about other things, like geography, also makes you shiver at the thought that these people are encouraged to vote.

However… Geography knowledge is probably something you can environmentally alter much more, if that’s what you want to focus on in schools. Well, hopefully. General knowledge correlates with IQ (anywhere from 0.30 to 0.62) so there is definitely a cognitive element to it which can’t just be pushed through. And that’s really the bottom line of this political agency business. Once you’ve taken the redpill and recognized that there is a large innate factor to learning ability and capacity, the thought of “voters need to be more educated” transforms into “these voters can’t be efficiently educated and should not be voting”. There is also, again, the factor of realizing most people will never give a shit about politics because having political ‘incelligence’ is not very conducive to finding a mate or achieving high status.

With this in mind, the Democrats head to the redoubt argument: on the grounds that the wisdom of the crowds will usually center on what is best for the collective, democracy is highly effective even if the crowd itself isn’t particularly smart. This was part of Aristotle’s defense of democracy, but it is not correct to apply it to the modern state. The wisdom of the crowds is a real phenomenon seen in things like competitions where people guess the weight of a pumpkin, or an ox, or something like that. People’s answers are generally wrong, but the average of these answers is closer to the actual weight than most of the guesses. However, this is only the case when people aren’t discussing their answers amongst each other. When people do discuss their answers, especially with things a little more close to home than the weight of a cow, the collective opinion quickly loses its predictive capacity.

Unfortunately, we live in a society where people’s opinions are anything but independent.

Read:

Surprise surprise, voters are not just making their opinions on intuition in the way they would when guessing the weight of an Ox, but instead imperfectly and in very viscous fashion fill the casts created by political pundits and elites. So… Iron Law of Oligarchy proven correct!

Now the Democrat falls to their third defensive line: “Democracy isn’t perfect, but it’s better than every other system. That’s why democratic countries have found so much success”. Which, like education, is a very cargo-cult mentality. The success of the West begins far before the creation of mass democracy, which in some ways was not even merely coinciding with the period of success but rather a direct product of technological and economic success. It was the European bourgeoisie, the same force spearheading industrialization, that first became inundated with liberal ideas, but that doesn’t mean that the latter had a significant positive impact on the former. Germany, for example, became an industrial power despite the failure of the 1848 Revolution. The Germans ennobled large amounts of wealthy burghers which helped stave off the sense of resentment which led to the catastrophe in France.

The first issue with democracy, from a utilitarian lens, is that it encourages the development of demagogic political religions which obscure good policymaking. Obviously, because we are not autistic goodie-two-shoes, such strategies are good when they benefit our political affiliates. But, they go bad a lot of the time too, and in an ironic twist of fate cause the unwitting masses to be wrapped up in the corrupt ideologies of ill-meaning elites instead of just letting them be. However, obviously I am not some sort of political eunuch who has no opinions on why democracy is bad of my own. I’m also not a utilitarian, but usually utilitarian arguments have a broad range when it comes to political decisions. The second issue with democracy, which applies even in an environment of people with adequate political agency, is that different groups have radically different interests which do not necessarily average out to something better than the sum of their parts. Instead, what you end up with is a patchwork of institutions designed for different systems. Nothing is working optimally because every election you end up with people who have different ideologies in power, who are implementing bits and pieces of their ideal system into the current state apparatus. This issue is already a problem in homogenous societies, because intelligent people tend to diverge on opinion rather than converge, but it is made 100 times worse in heterogenous societies. Aristotle brings this up in his defense of democracy as well, that democracy works when the voting body is comprised of a single ethnic group with a shared culture. Otherwise, different groups naturally descend into an arms race of identity politics, taking advantage of their higher-principled peers. You may have seen this picture before:

This is from Guillaume Faye, a right-wing ideologue who you might be familiar with from his other writings. While Faye is correct here, Aristotle’s concept of philia applies to all faculties of life. Class-based grievances are also easily taken advantage of by demagogues, who encourage forms of anti-elite resentment among the masses in order to bolster their vote. This would not be as terrible of an issue in a society without democracy, because officials are not constantly trying to woo the masses. But yes, other major factors for the lack of philia are ethnic, physical, cultural, linguistic, and religious differences. I would say that the simple factor of country size and population also plays a role.

And what about the differences in gender? All societies got around this historically by not allowing women to vote. It doesn’t make sense to let women vote because they are in the house, they don’t really operate in society in the way men do. They influence politics through influencing their husbands, through leveraging their vaginas and whatnot. But today, a lot of women are in society, and among these women those who couldn’t find a man were often the ones becoming feminists. And they either end up adopting the political views of whoever they marry, or they get old and angry that they can’t use their pussy power anymore and decide to channel it into politics.

What about other political systems? Well, they all have their problems, but we have already established that democratic regimes do not meaningfully represent the interests of the people because…

…Well, some of the people are retarded. Some of them are semi-retarded. And some of them are quite smart, but aren’t gonna waste their smarts on a socially corrosive, useless hobby. Maybe if you were rewarded for being a smarty-pants with more power over the system…

First, let’s start with something close to home, both figuratively and literally. In the early United States, only land-owning White men were given the right to vote. This would effectively serve as a filter for some of the less affluent white men who are part of the aforementioned “politically blind” majority. You also add some philia back into the system this way, through having a more homogenous body politic. However, there is a problem that “land ownership” is a very arbitrary standard. Especially today, plenty of fairly successful and upstanding people don’t own land, and may get the shitty end of the stick from not being able to vote. Some of these people are doing much more good for their country than a land-owner.

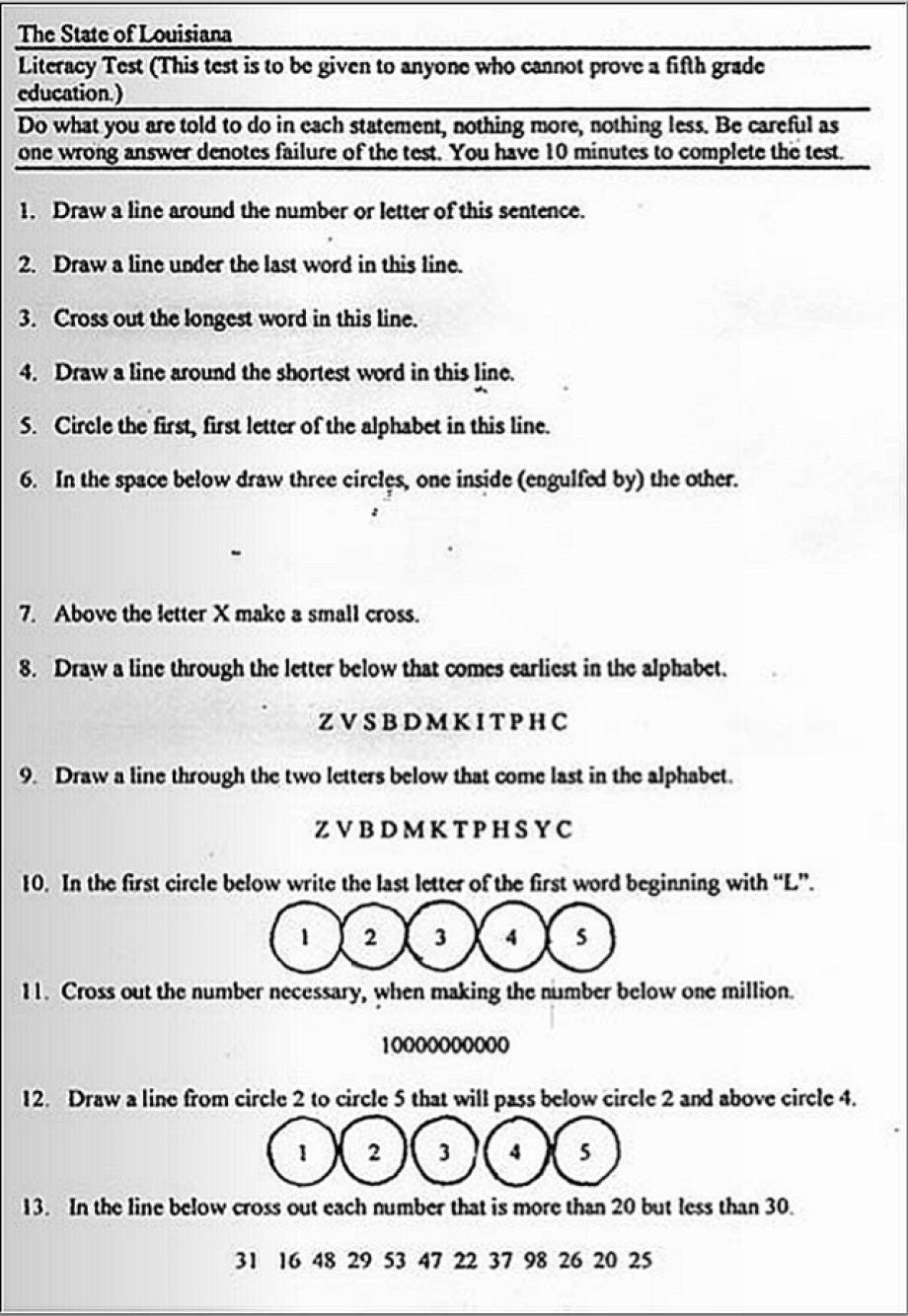

Another practice seen in the united states was the implementation of literacy tests. This is a good policy, and literacy tests were no where near as confusing as people act like they were. Try it yourself:

Sure, some of the questions are a little sneaky, but as long as you read them carefully they aren’t too bad. I think some people view this as messed up because it’s called a “literacy test” when in reality it is more of a very short cognitive test that you have to be literate to do. But, you really want voters to be able to pass this. It doesn’t really solve the other issues of democracy though — the careless voters, the dangers of politicians riding social divisions, the general lack of synchronization in the state apparatus. There is also a fifth issue, which I’ll get into when I get to Monarchy.

The second system is oligarchy and the development of political castes. There are two forms of this I would like to discuss. The first is the system of aristocracy, where politics is headed by elite families with military leadership. The second is the one-party state. I believe that Aristocracy was the best form of government, but right now does not make a lot of sense. What is the best form of government right now is probably a one-party state or a limited democracy like I discussed before. Aristocracy is the best form of government because the Aristocracy is the life-blood of civilization. I believe that civilization emerged in the same way the mitochondria emerged. The aristocracy is initially its own group or some clan which takes over a larger collective group, and uses the productive class to generate high culture. People misunderstand the Bourgeoisie as being parasitic, when in reality they are not parasitic enough. The purpose of civilization is culture generation. It has never been primarily about improving standards of living, something you really have to have gone through a bit of an Anprim phase just to understand. The bourgeoisie is not very good at directing their wealth towards this end, they always put it back into the market. Or they spend it on something stupid and vain. Their frugality is fair, because the bourgeoisie lose their money fast. Intergenerational wealth is usually fleeting. The Aristocracy derives its wealth from the shares it owns in the state itself, in the military control of the land, and in return provides military protection to the peasants.

However, there are some problems with the aristocracy. Namely, it doesn’t really exist anymore. Aristocrats do not have much of a place in modern society due to the aforementioned differences in militaries, and due to the unmatched wealth which can be derived from commercial enterprise. I believe that the one-party state, however, re-establishes the aristocratic principle. Ironically, under certain populist strains. I will explain why the aristocracy has an incentive for good statecraft… When I get to Monarchy!

In the one-party state, the uniparty has a similar position as the aristocrats of yore. It is not technically part of the state, but it has an uncontested grasp on power in the state and hence does not have to compete for votes. The Aristocracy also shares the monopoly on violence with the state through the use of paramilitaries. So it functions as a state within the state. The one-party state is fluid enough that public unrest can inspire party reformation in a non-revolutionary manner, but rigid enough that it can maintain a consistent telos and ideological grounding. The party is something of a clique in the same way the aristocracy is, but unlike the aristocracy their share in the state is entirely mediated through the party rather than through their own ownership or a lease from a higher feudal lord. Now obviously, I would rather a thousand times over be in a conservative democracy (*actually* conservative, not what we have today) rather than a communist one-party state like the Soviet Union. I hope nobody’s takeaway from this is that a society *needs* to have any of these systems to survive.

Problems with Uniparty… Corruption? Ehh, I don’t think corruption would necessarily be more common in an austere uniparty than in a democracy. Plus, it probably pales in significance compared to inauthentic decision-making of democratic politicians in order to get votes. Straying from party line, schisms? Hmm, could be an issue. But usually when the uniparty does this it is because A) their ideology is retarded (communism), or B) they are under the influence of some foreign power and cannot act naturally. The uniparty is still inferior to the aristocracy because bureaucrats are annoying people and gutless, but perhaps with this system you can begin the process of recreating the aristocracy. How interesting!

We want our uniparty to be built on political myths, what Plato calls “noble lies” but we don’t want to use that dirty word. Obviously these political myths cannot subvert the existence of the uniparty itself, so “democracy” can’t be one of them. Other things though, like liberty, freedom… Well, let’s just cut to the chase and get to Hoppe! I know some of you have probably been salivating for this.

Hans Hermann Hoppe is not the only Libertarian thinker to reject liberal democracy, but he is the most famous. Hoppe’s argument seems strange on its face — why would a Libertarian want an autocratic leader? Well, it is strange, until you realize that a monarchy is actually just a privatized state. Which brings me to Hoppe’s first point against liberal democracy: Rulers have no share in the long-term outcome of their policies. This is especially true when leaders have term limits lasting only a few years. Civilization is a project of people doing hard things because eventually it will pay off. This is why we farm, why we raise livestock, why we build shit… But, what encourages long-term statecraft in a liberal democracy? The politicians probably won’t be in office in 50 years. They’d be lucky to be alive in 50 years. And if they make policies that will benefit us in 50 years, but have an immediate negative effect, it will be used to inspire the (again, not very high-agency) voters to turn against them. This is a problem in corporations too, increasingly. A Monarch, on the other hand, has to keep a country in good condition. Because his son, and his grandson, and his great grandson and so on are going to inherit it. This is the same mentality which encourages aristocrats, who can be considered “little monarchs”, to better the country as well. If the state is maintained terribly, the future monarch might get his head chopped off. Not even necessarily by revolutionaries — often by the nobles below him who then start a new dynasty or import a dynasty. If the monarch creates a country that is serene, but not powerful, he can get conquered or his country subverted by a foreign power, causing him to lose his titles. This is all very much like a real private company, although I have argued in the past that it may not apply to corporations and managers.

So, the Monarch has a very strong incentive to do proper statecraft. The Monarch is also probably decided under better auspices than a democratically elected leader. First of all, the royal line is a very well-maintained family, eugenically speaking. If the queen pops out a good amount of kids, one or two of them are bound to be quite gifted. The main problem that arises here, is succession. Agnatic succession is good for stopping your sons from killing each other, but doesn’t take full advantage of the benefits of royals having very high fertility. I don’t know how much fratricide would be a factor in a modern monarchy — people are generally less homicidal now than they were in the middle ages. The prince receives the best education, and is so wealthy and powerful that he cannot possibly be bribed unless the bribe involves expanding his political inheritance (which is a good bribe). Everything that goes wrong is ultimately blamed on the Monarch, because his power is absolute, unlike in a democracy where problems can always be blamed on the former administration, or the legislator, or whatever.

Which gets to point number 2, that the monarch makes it perfectly clear that you are not part of the state, and cannot control it or change it. Hoppe, as a Libertarian, was very concerned with state overreach, and viewed Democracy correctly as a disguised oligarchy (all systems tend towards oligarchy, because again most people lack political agency and political interest). But what makes mass democracy so sly is that it gives the people an illusion of choice. When in reality, as I alluded to earlier, the elite is largely responsible for what decisions get made and the people just follow along with this. Every four years we have our fake revolution to let off some steam, and we have our fake little doll-house rights. On this point, I think again, if the state is a righteous state then it is not bad to have a totalitarian state, but if we are not assuming anything about the state then this is a good argument for monarchy. This also means that the state is less likely to get in extremely devastating wars because the state is recognized as a ruling entity divorced from the people. Now, I don’t think this is entirely true. A lot of Monarchist theorists have very strongly emphasized the king as a crystallization of the entire nation, and more importantly (and I think Hoppe would agree with this) we don’t live in a monarchist world anymore so monarchist states need to have this sort of ferocious devotion to the state in order to compete with ideology-brains.

I will add another bonus to Monarchism which I don’t think Hoppe ever discusses, but if you’re an environmentalist you should like it. Aside from just being patrons of the arts, Monarchs also like to reserve a bunch of lands for their own personal hunting.

Hoppe makes very good arguments in favor of Monarchism, and I think monarchies are actually one of the more Libertarian forms of government due to the concentration of the state in one man. Simultaneously, it avoids the pitfalls of Libertarianism by having a strongman to repel subversion attempts, but I don’t think it does it good enough. In the modern world, the ideology-brains will come for you, so you really need to be proactive and develop some dogma of your own.

I have never read Curtis Yarvin’s Patchwork book, but I think I would like it. So, maybe I’ll read that and get back to you guys.

I have a principle I call the free market paradox. Which is that if a market has no government interference, a few corporations can consolidate power and bribe the government to impose regulations. If the government does interfere with the market, the biggest corporations will bribe the government to impose regulations that help the big corps. The only way to stop this is to create a class of people who are independent from the market, who have the power to regulate it. For most of history, this is the aristocracy/military or the clergy (in more religious societies). Democracy does not have this because politicians cannot gain popular support without campaign funds and media support. This is the fundamental failure of universal democracies. It's also why Hman gave so much power and parallel functions to the SS. They were meant to become pagan aristocrats who could break the influence of the German corporations and clergy.

The thing about your comment about land ownership, if the right to vote was tied to land ownership then certain talented people would prioritize becoming landowners in a way they aren't now.