There is an old saying about the Italians and the Greeks. “One Face, One Race”. Nowadays, most Italians and Greeks would like to believe it. For the Greeks, it further legitimizes their claims of Roman-ness. For Italians, it cozies up relations with the nation across the Adriatic after the disastrous Italian invasion during World War II. In a previous post, I discussed the degree of Greek ancestry in Italy, which most likely comprises an outright majority in the South.

A Song of Polenta and Pizza: The North-South Divide in Italy

It’s no secret that Southern Italy diverges from the North in many ways, and usually for the worse. It has a lower GDP per Capita, it had high birth rates for longer and is today younger than the North, but no longer has unilaterally higher fertility rates

The story of Italy and Greece is not so simple as a history of mutual respect. It is a tale of brothers, but step-brothers or half-brothers. It is a three-and-a-half century long Drama as tumultuous as the stormy seas that these brothers worshipped together and conquered separately.

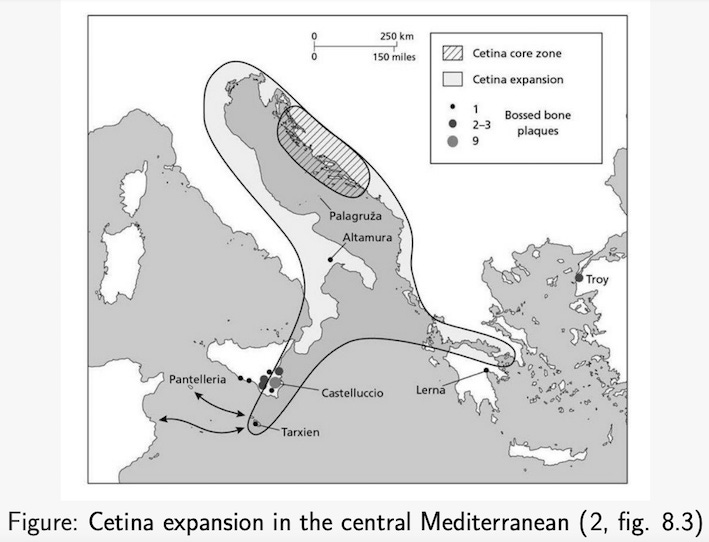

Our story begins in the Middle Bronze Age. Balkan colonies of the Yamnaya-descended Catacomb Culture arrive in Northern Greece around the late third millennium BC, some time after Beaker Folk begin settling the Italian Peninsula. The Italians and Greeks do not descend from the same group of invaders. In fact the Italic languages are closer to the Celtic and Germanic languages, and possibly even the Indo-Iranian languages, than they are to the Greek language. When Italic arrived in Italy is unclear, because Italy had various non-Indo-European and non-Italic Indo-European languages by the Iron Age, when Italian history begins. Italy would be invaded from the North not once, but twice. First, with the Bell Beaker expansion, and second with the expansion of the Urnfield Culture in the late Bronze Age. The divergent origins of the Italians and Greeks was, throughout the Bronze Age, mediated by strong networks of cultural exchange and trade which crossed the Adriatic, and sometimes even the Alps. The Cetina archaeological culture, likely a product of Beaker Folk who had settled in Dalmatia and mingled with the preceding Vučedol Indo-Europeans. I suspect this is the source of Corded Ware/Bell Beaker derived ancestry that arrived in Bronze Age Greece after the initial Catacomb-like input, and the Northerly shift that Greeks from late Bronze Age Mygdalia and Amvrakia have relative to other Mycenaeans. This ancestry did not necessarily come dirctly from Cetina-descended people, but perhaps also from the Amber merchants from further north who stimulated the Cetina Culture. There is a man you know very well who would have lived in the wake of the Cetina Culture… He was a man of many devices… Of plots, of twists and turns, a sacker of cities, the baffler of the wretched suitors… By the time of the Trojan War, it was no more, but I’m sure the population of Ithaca was influenced by it genomically.

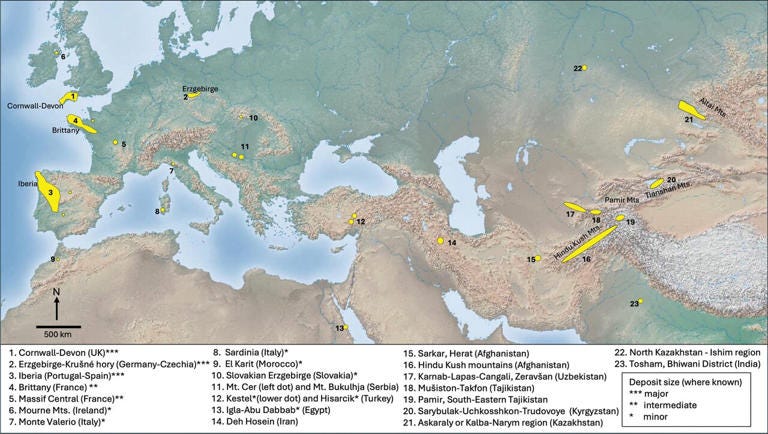

Movement wasn’t just going on from north to south. It is likely that Aegean elements entered Italy, particularly Sicily, before the city of Troy was laid to waste, and before Ugarit was set ablaze by the Sea Peoples. There was a minor Zagrosian-related or CHG-related introgression across the Mediterranean during the Chalcolithic. It most famously impacted the Minoan and Helladic inhabitants of Greece and Crete, and CHG-related ancestry likely cropped up there in the early Copper Age, around the same time it began to surge in Anatolia and the Levant. Around the end of the 3rd millennium BC it arrives in small amounts in Southeastern Spain and Northern Italy, and in Sicily it is a pronounced component by the middle second millennium BC, at a greater proportion than what is found in Spain and Northern Italy. As far as sea-wide gene flow goes, this was probably related to the extensive tin trade that supplied the Hittites with tin from Bronze Age Britain, France, and Spain. In return, manufactured bronze items were dispersed from Cyprus and the Aegean world into the Western Mediterranean. The British were actually the first in Europe to use proper tin Bronze, which eventually replaced the Arsenical Bronze of the earlier Bonze Age.

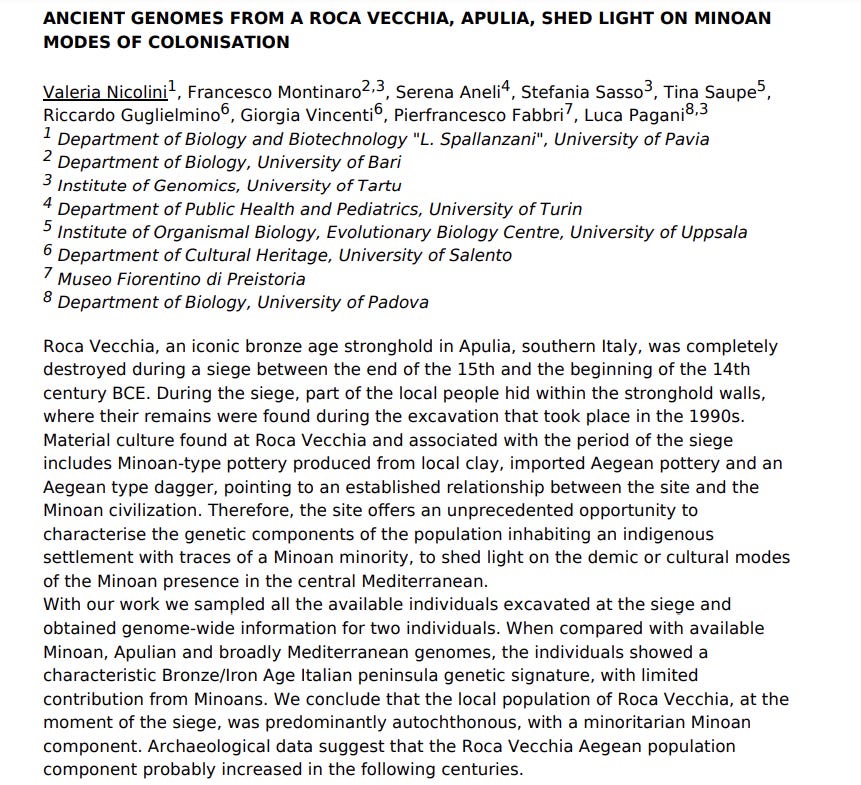

Anatolians were not a colonial people. The Minoans and Mycenaeans were more adept seafarers. The Minoans, before the arrival of the Greeks, had successfully colonized parts of Cyprus and the Cyclades, and likely had a presence in Miletus before the Mycenaean and later Ionian arrival. The Thapsos Culture in Eastern Sicily likely represents an early Mycenaean Greek intrusion, predating the colonies of Magna Graecia by many centuries. Strabo reports that Greek colonization of Southern Italy began before even the Trojan War, and this may have been the source of such a claim. It also appears that the Minoans or some heterogenous group of Minoan-Mycenaean raiders may have besieged and taken over an Italic fortress in Apulia, one that was already somewhat Minoan-influenced. There is allegedly an upcoming genetic study confirming this, but the abstract is private right now and all I have is this picture of it:

The desire for Tin and Amber from the wealthy Eastern Mediterranean civilizations fostered a class of warrior-mariners that would eventually come bearing spears and axes to the illustrious oriental cities that they had previous supplied with the precious stones of the north. Today we call them the Sea Peoples. It is, at this point, a matter of fact that many of the Sea Peoples were Greeks and Luwians, one of them being the Philistines. The Phrygian and Thracian invasions of Anatolia could also be considered part of the Sea People migrations, despite mostly occurring over land. The evidence for Western Mediterranean is shakier, traditionally reliant on tenuous etymological connections (Sherden-Sardinian, Shekelesh-Sicel) and similarities between the horned helmets and armor of the Sea Peoples with Nuragic and Iberian warrior depictions. I have also heard that the swords depicted among the Sherden were similar to Nuragic swords. The Egyptians describe them as a group descended from various Islands to the North, various nations united in pillage, and I’d imagine that the slavers and pirates of Homer’s Italy wouldn’t have missed out on such activities. The Sherden actually ended up forming a large swathe of the Egyptian army in the years following the Battle of the Delta, which suggests that although they lost the battle they ended up impressing the Egyptians.

When the rest of Europe was reeling from the catastrophic Bronze Age Collapse, the Italian Peninsula began its rise out of barbarism. In the Western imagination, Etruscans and early Romans are a Hellenized people who derived their civilization from the Greeks. It is an entirely untrue outlook that, like the belief in an Etruscan or Roman origin from Troy, is based on taking a later convergence and placing it in the mythic past. Etruro-Italic Civilization originated north of the Alps, likely entering Italy in its embryonic state through Pannonia, and began after the establishment of the Urnfield Culture in Italy. The Italics and the Etruscans were not like the Greeks. Their religion was not the Greek religion. Their gods were not the Greek gods, and the equivocation of Greek and Roman deities in later Roman history was highly damaging to Roman paganism. The Greeks were pirates by nature, merchants by circumstance, and intellectuals by some divine miracle. Their gods, like the gods of the Norse and the Indo-Aryans, were subject to humanization, and greatness was to be achieved either through heroism, on the battlefield, or through the mysteries, under shadow. In my opinion, early Greeks were much more pastoral and carnivorous than historians suggest. The diet of the Homeric warriors is almost entirely carnivorous! The Italics, on the other hand, were more agricultural, albeit it depended heavily on the region. The Samnites, for example, were more pastoral than the Latins. Most of their early deities were related to agriculture. Even Mars, who we know now as a war deity, was initially more associated with the agricultural side. Their gods, along with the gods of the early Etruscans, were invisible forces which one saw only through their traces in nature (for example, Jovian lightning). Several Roman divinities seem to have been euhemerized into historical human beings or demigods as time went on, as many myths which involve the gods in other Indo-European religions involve men in the Roman histories. It is possible that early Roman divine mythology was simply ill-preserved, albeit, as much of our records of early Rome are histories coming from a point where Greek and Roman religion had already begun fusing. The greater abstraction of divinity is quite clear-cut, though. Numa, the second King of Rome credited with many Roman religious norms, was not very fond of icons of the gods. Where Greek religion was interwoven but decentralized, both Roman and Etruscan religion were organized by a much more coordinated class of jurisprudent priests who kept extensive literature on the precise way to engage in rites, festivals, and divination.

The origins of Italic civilization during the Greek dark ages undermine the idea that the Greeks brought the light of civilization to Italy, and yet they eventually did outshine the Etruscans as the primary influence on the Roman intelligentsia. It first came through the gods of travel — Apollo, Hercules, and the Dioscuri, entering Etruro-Roman religion. Then, the Romans adopted a set of holy oracular texts from the Greeks that became known as the Sibylline Books. As Etruscan civilization weakened, the Romans were forced to look south for guidance, towards Magna Grecia. Nevertheless, the Romans segregated their gods from those of the Greeks for many centuries, until they accepted the Greek gods into the city gates after their defeat of Hannibal and their conquest of the last free Greek state in Italy.

Magna Grecia ballooned in size and prominence, but not in area. By the Hellenistic period, Syracuse was the largest city in the entire world, and yet Sicily’s inland was still dominated by native Italic and pre-Italic tribes. The extent of intermixing between the Greeks and Sicilians (who were, in fact, three peoples at the time) is difficult to assess, because the Greeks were already genetically similar to Bronze Age Sicilians and Greeks came to the Island from many different city-states, and Greek colonies in Sicily were of multiple origins.

All of the vices of the east which the Greeks had picked up in their Alexandrian tour would begin to enter Rome, to the dismay of many Conservatives. Greek religion had previously served as supplementary to the Roman religion, just as Etruscan religion had. After the Punic Wars, however, the combination of Greek and Roman deities had stripped many of the unique qualities of Roman deities, and the introduction of eastern mysteries encouraged dissent from the state religion. It is, at this point, that the entirety of Magna Grecia had been conquered by Rome.

Many people incorrectly assume that the Romans were all Philhellenes, but it isn’t true. There were some Hellenizers, like Scipio, but then there were some who viewed Greek influence as corrupting Roman traditional culture with their luxuries and philosophy. This is what Cato the Elder has to say about Greeks:

“[Greeks] are a most iniquitous and intractable race, and you may take my word as the word of a prophet, when I tell you, that whenever that nation shall bestow its literature upon Rome it will mar everything; and that all the sooner, if it sends its physicians among us. They have conspired among themselves to murder all barbarians with their medicine; a profession which they exercise for lucre, in order that they may win our confidence, and dispatch us all the more easily. They are in the common habit, too, of calling us barbarians, and stigmatize us beyond all other nations, by giving us the abominable appellation of Opici. I forbid you to have anything to do with physicians.”

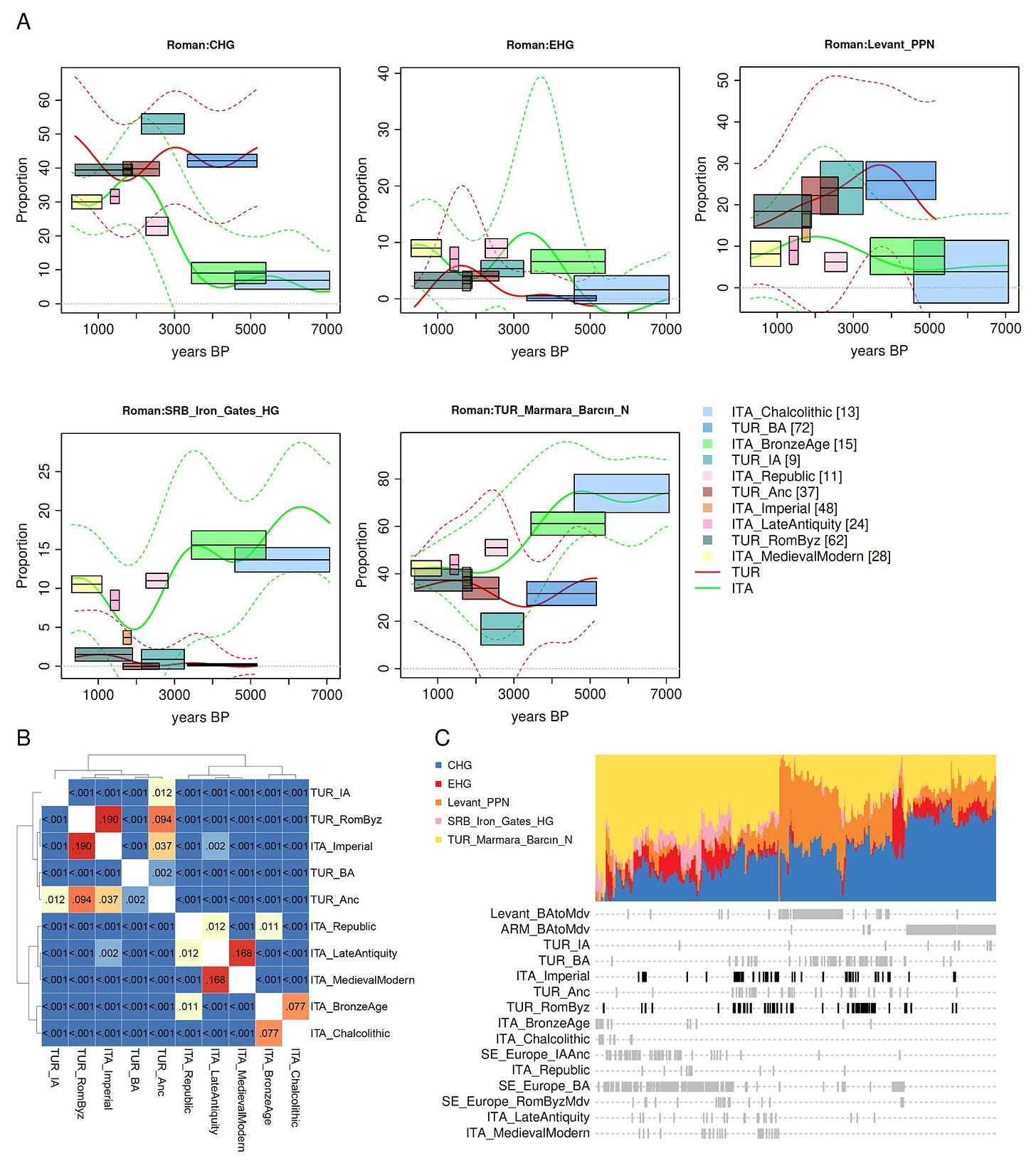

Plutarch confirms Cato’s anti-Greek sentiment beyond the realm of doctors. He didn’t like their philosophers, their vanities, or their nudity. Cicero is another famous Roman who had some less than pleasant things to say about Greeks, especially Asiatic Greeks who he considered far inferior to mainland Greeks. This was, keep in mind, after the Asiatic Vespers, where tens of thousands of Roman civilian colonists were systematically slaughtered by a Hellenized eastern warlord. Other Romans, such as the consul Manlius Acilius (according to Livy) and the satirist Juvenal, also made this distinction between Greeks of the mainland and Asiatic Greeks. By Juvenal’s time, though, these Asiatic Greeks from Anatolia had become the predominant population of urban Italy (as Juvenal himself laments). This became the case in Greece as well, most likely, but only after the Roman conquest. Samples from Tenea and Amvrakia remained genetically similar to their Classical ancestors during the Hellenistic period, but Imperial-era samples from Tenea are genetically similar to the Roman-era Anatolian population that also dominated Roman cities at the time. The Roman attack on Corinth was especially devastating, resulting in the wholesale slaughter of the city’s male population, so it is possible that Corinthia (and subsequently Tenea) experienced a more sudden population overturn than the rest of Greece.

According to Hesiod, the Tyrsenians descended from three children of Odysseus and Circe, making the Italic tribes of Greek origin. The Romans eventually adopted the myth that they were of Trojan origin, as we all know, and it was also well-established that the Latins were of Arcadian origin before the arrival of Aeneas. These are both, most likely, completely fabricated events, but in an ironic twist they ended up coming true through the mass importation of Anatolians and Greeks into the city of Rome. Rome and Greece, at least in their urban settings, had genetically converged, but this convergence would not last for long. The Roman urban population collapsed during the late Empire, with the Eternal City itself dropping from around 1 million people to under 100,000. The Anatolian genetic profile was dropped with it, as rural and less admixed Romans repopulated the devastated cities. It would last for some time longer in Greece, but was broken by the Slavic invasions and the plague of Justinian.

The Trojan identity may have coincidentally mirrored changing Roman demographics, but more intentionally it served as a way to distinguish the Romans and give them a prestigious history juxtaposed to their Greek rivals. This Trojan anti-Greek identity would survive well into the middle ages, being taken up by Celtic and Germanic kings of the West. Dante, being the proud Italian that he is, of self-proclaimed true Roman blood, also strongly identifies with the Trojans and against the Greeks. Odysseus, Achilles, and even the noble Diomedes are burning in hell, while Hector is in Limbo and Ripheus is in heaven.

After the Slavic migrations, there were not really any changes to the ancestral makeup of Greece and Italy. If the Turks and Moors had an impact, it was marginal. The fall of the Western Empire brought about a gradually worsening relationship between the Greeks and Italians. I have discussed this before, but the Byzantines played a major role in the de jure end of the Western Empire. During the Ottonian era there was already no shortage of Westerners snidely calling the Byzantines the “Greek Empire” rather than the Roman Empire, and this greatly upset many Eastern Emperors. In the wake of the Schism, there was no sense of cultural unity between the Greeks and the Italians. Not only did the religious divide rend Christendom apart, but the Byzantines were increasingly drawn into conflict with the expanding Normans and Venetians. Italian merchants made up a large minority in Constantinople, an were viewed by many as parasitical and excessively privileged, culminating in riots which killed 40,000 Latins in 1183. On the other side of the Adriatic, many Italians viewed the Greeks with similar distaste. They were not only schismatics, but pretenders. To the Venetians, the true Romans were those refugees of ancient Patrician families who had fled the Lombards to found Venice in the marshes. The Byzantines were not the restorers of the world, but the modern Mithridatic Army coming to purge Anatolia of Romans. Many stereotypes about the Byzantine Greeks, that they were decadent and soft due to luxury, were also Roman stereotypes about the Greeks during antiquity. Dandolo’s decision to destroy Constantinople was motivated by the anti-Greek sentiment of his fellows along with his personal vendetta against the empire that had reportedly blinded him decades prior. And yet, it would be the Venetians who would provide the most ships to the Byzantines in their final moment. The threat of a Turk-ruled Eastern Mediterranean had been productive in mending the gap between the races. The decades before the fall of Constantinople were the closest that the Eastern and Western churches had ever come to mending the schism. Many Greek scholars and nobles fled to Italy, bringing with them classical and Islamic literature. It is not true that they started the renaissance, but they did contribute to it, especially among Humanist philosophical circles.

In the stead of a Greek state, the Venetians and to a lesser extent the Genoese became the primary Christian power in the Aegean and Adriatic sphere, occupying many islands for centuries but unable to control any land in mainland Greece for a long period of time. However, after these territories came under Greek control most of the Italians living there left and went back to Italy. Some Italians also settled in the Dodecanese in modern times, after they took the islands from the Turks, but they left as well after World War II. Greeks in Italy were mostly done away with through gradual Latinization beginning under Norman rule, but some communities still exist today and are genetically the same as Southern Italians as far as I know.

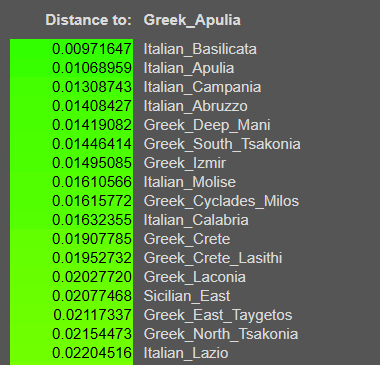

Mainland Southern Greeks are close to mainland Southern Italians, but due to divergent sources of northern ancestry mainland Northern Greeks are more close to Balkaners than Italians and mainland Northern Italians are closer to Spaniards and Frenchmen. So, “One face, one race” is only half-true.

I don’t have much of a way to end this. I kind of was gonna abandon this post but I thought the cover picture was too hype and aura moment, so I am posting it. Hope you all have a wonderful day

I'm intrigued by your comments on how different Roman religion was from the Greek. Do you think you can write more about this? Also, can you recommend any books on the subject?

Thanks.

I once heard someone say " the genetic differences between an Anglo-Saxon and Southern Italian are greater than the differences between a Syrian and Southern Italian" and

"A Somali is MUCH LESS distant to an Anglo-Saxon than to a Nigerian due to Western Eurasian ancestry"

Thoughts?