Ver. 1.3

A long time ago on here, I wrote a response to Traditionalist’s criticism of Wignat Pagans. In it I gave some criticism of the “Traditionalists”, mainly that they cherrypicked certain religions to fit their ideas and rejected the rest as either exceptional or decadent. Basically, each religious tradition reflects a certain weltanschauung of its own people, and the idea that they all converge towards one truth seemed not only irrelevant to the truth but unlikely.

However, I’ve recently been reconsidering my views on this. Actually, I think that Perennialism is quite reasonable, but it does concern itself a bit too much with the scholarly and innovative religions of the Axial Age and onwards. Believing in these innovations is not bad, but there is little evidence that it is a “Tradition” world-round. These religions no longer represent the intuition of a national genius, but a motivated ideological school which the intelligentsia can devote themselves to defending and expounding upon at all costs. This clouds the true purpose of Tradition, which is that it provides evidence for a sort of “common consensus” argument. If everyone simultaneously thought of this idea in many disparate cultures, it might just be the sort of self-evident truth that an unbiased, unconditioned person would adopt. This is a common informal argument for the existence of God, but I would like to maybe stretch the scope of it a bit further. The best source for Tradition cannot come directly from philosophers or reformers, like Plato or the Buddha or Zoroaster, although I do not think any of these men run contrary to it even if at times they run contrary to each other in one way or another. More importantly, what they have in common with the tradition is simply an abstraction of what was already mystified and poeticized in myth. It is preferable for evidence of the tradition to come from myth itself, stories designed to endure the tests of time, like a seed silo that preserves an esoteric knowledge waiting for those who contemplate, while having a tough exterior suitable for proliferation among the general population. That being said, I will be arguing that the perennial tradition does argue in favor of a roughly Platonic cosmology.

First of all, there is one intrinsic attribute to most religious traditions, almost by definition of it being a religion: Idealism. Idealism in the loosest sense, that the physical world is underlaid by another world which is spiritual, psychic, and/or ideal in nature. This is the basis for some of the world’s oldest and most primitive religious traditions, such as animism and shamanism. After all, if all phenomenal objects are underlaid by this sort of “soul” or “essence” then to worship these objects as if they are ensouled like we human beings is only natural. There are some odd cultures which seem to not actually have a religion, but these are few and far between. It is unclear when exactly human beings evolved the mental capacity for religion, although some Buddhist sects consider animals to be in a state of constant religious enlightenment. Elephants, one of the smartest non-human animals, are known for having funerary rituals which do not serve much of a practical purpose.

I would expand the scope of this idealism and propose specifically that traditional religion participates in a specific kind of idealism I would call intellectual realism. Firstly, it places the intellectual agent prior to or in equal standing with the anima or will. Secondly, it supposes the existence of substantial form.

Secondly, I would include a few other elements which surface across the cosmogonies of Eurasia. Firstly, is the idea of the universe arising from an unqualified, simple, ineffable substance. This is often referred to as Chaos, but also takes the form of things like cosmic eggs. Secondly, the creation of the universe comes with the splitting of the universe into two primary forces, the ideal world of thought, form, order, with a sort of residual sludge of ambiguous receptive substance. This can be referred to as hyle, but I wouldn’t necessarily equate it with matter. It must be recognized that matter is necessarily a combination of form and hyle, even the smallest types of matter have to have form to them, or else how could we possibly identify and interact with them? hyle, I think, can be more accurately be called Prima Materia, disorder, entropy, change (particularly change which involves a dissolution of properties), and to philosophical schools it is perhaps similar to the Indian Prakriti and the Orphic-Platonic Ananke. Later Platonists even go as far as to disregard Ananke and equate it directly with the Anima Mundi, or world-soul. The character of this substance, for obvious reasons, is much more difficult to elaborate on and holds something of an association with evil, but that word is very loaded and I’m not sure if I would use it here if not for convenience.

The receptive substance must exist, in a monistic sense, because the monad is immune to privation. You will notice, as I lead through examples, that nothing is actually created ex nihilo. Actual nothingness or nonexistence cannot be the object of privation because you can’t deprive something of nothing… x ± 0 = x. The intellectual agent is seemingly the primary being-sub-Being, though, which is not (as far as I can tell) inconsistent with the privation view.

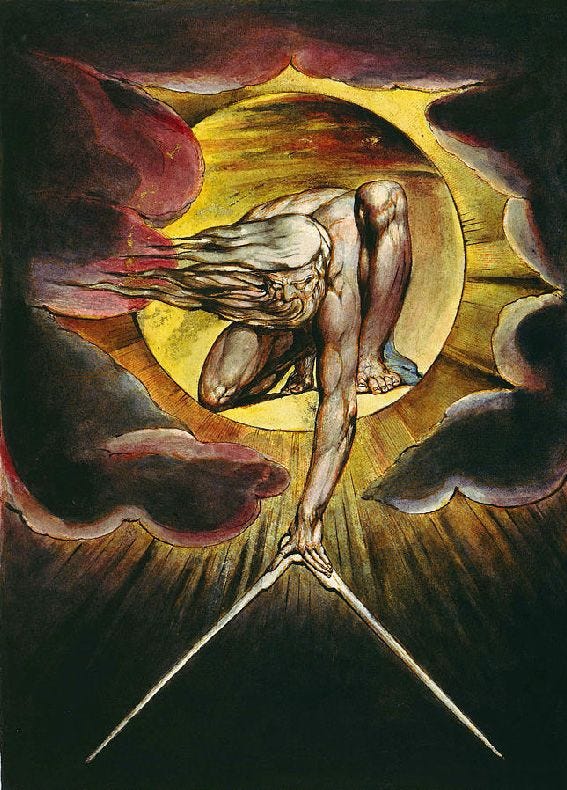

The world is then formed by something of a recombination of these two substances — a redemption of the latter by the former. Matter is a hylomorphism, a combination of form, essence, idea, with substance. The demiurgic intellect triumphs over the residual chaos in the struggle that is known as the Chaoskampf, and beats it into form. Through this, the world is ultimately naturally ordered and human beings are made more good than bad, although through the ignorance or willful malevolence and malice of free agents can chaos triumph. The residual existence of evil (which I hesitate to call it, it’s not necessarily evil) also causes a problem nonetheless, it is something we have to deal with in this world. It preys upon greatness, but also upon itself, which causes a sort of sine wave in the pattern of order and chaos.

I would argue that there are two major differences between this “orthodox” mystified view, and the religious views which developed during the Axial Age and late Antiquity. Firstly, the tradition preserved in myth is not focused on soteriology. This is not to say that it didn’t exist — it does, in the form of apotheosis, but a certain anxiety about life is not yet present, a restlessness. It isn’t even that there is a great deal of effort spent defending life in this world, it just isn’t really considered a point of contention in the first place. All that is necessary is explaining the transcendent elements of this world, and the nature of goodness in this world and beyond it. Secondly, the process of “overcoming” the decadent element of the material world involves active participation in the world, rather than an inactive renunciation of it. Active participation may coincide with an emotional renunciation of it, but not an active renunciation in the way of monastics. This active participation in the world is most strongly demonstrated in the widespread practice of heroic cults. Heroes, essentially, attained a sort of godhood by mimicking the creative destruction of the Demiurge and by establishing themselves so heavily in the minds of people that they evolve into a sort of transcendent archetype. Bards, and by extension all artists, as well as priests, also represent this role to a strong extent. There is also one minor and unclear difference, which is the eschatology and nature of time in Traditional societies. It seems to me like ideas of “cyclical” and “linear” time come later, and may have been left somewhat ambiguous at this point, but it may have erred more towards the former. As a sidenote, some schools which developed both in Western and Eastern philosophy do away with the conditional duality of this system, particularly with respect to discrete forms.

Also, I would like to mention two moral standards which seem to basically be held in high regards everywhere on earth: Hospitality and Oath-keeping. In some sense, oaths can be considered as the atomic unit of Pagan morality, because in breaking an oath you are engaging in an act of self-contradiction. You are doing the opposite of what I just described as the goal of traditional religious life. Hospitality is popular for less significant reasons, but even today if you go to any more traditional part of the world you will be surprised at how certain savage peoples like the Afghans are actually extremely hospitable. Hospitality obviously serves a good purpose as a sort of social contract in a time before hotels or high-speed transportation, but it also serves as an opportunity for people to demonstrate virtue. The wealthy man who has virtue yearns for a weary traveler, because suddenly he can demonstrate the goodness of his house and hearth, just as the knight-errant who has virtue yearns for battle, so he can demonstrate his courage and athleticism. Hospitality requires more introspection, it also serves as a sort of building block of morality in ways that are much more complicated than “social contract”, but that’s for another post. The relationship between guest and host could be considered the most basic component of righteous relation between people within society, from it you can derive other things like the patron-client relationship.

Now, I would be doing nothing but blabbering if I didn’t talk extensively about these myths in cultures worldwide, so that’s what I’m going to talk about for the bulk of this essay. But mainly, we’re going to focus on Eurasia and North Africa, and particularly on the cultures in these regions which gave rise to high civilization. Firstly, it is simply more convenient to work this way. Africa and the Americas are much more linguistically diverse and have various obscure groups to catalogue. It is really quite shocking how many unrelated language groups exist in the Americas considering the continent was only settled by its current population over the past 20,000 years. Secondly, it is mainly within civilizations that a religious high culture is maintained and contemplated professionally. For this reason, it is difficult to source things from parts of the world which were still in more of a stone-age modus operandi by the time we record their myths. I trust that, given my audience, I will not be lambasted as a “Eurocentric” for saying this. I will try to include some discussion about myths from these groups, but a lot of it is inseparable from superstition and in these more tribal environments it is not uncommon for people to develop very strange cultural quirks. I suppose this does generate some bias, there are religions which are more conducive to civilization than others are there not? And in this sense we are seeing memetics at play? Well… Yes, but I would say that civilizational religion is actually less biased than primitive religion in this context, because more primitive societies rely more on custom for maintaining social order. They do not have the economies or bureaucracies or militaries to maintain order mechanistically. A good example of this bias comes from the “Guilt-Shame-Fear” division of human societies. Fear-based cultures generally exist in populations living very primitive lifestyles such as in the dense forests of the Amazon, Papua, and Central Africa. This is not much of an endorsement for the G-S-F model, just an observation of what areas are apparently most fear-based. In a lot of these scenarios fear cannot be instilled through threat of human force alone, but it can be instilled through the promotion of superstitions.

The way I’ve opted to do this is whole project to talk about examples from the major language groups of Eurasia, and then afterwards maybe some additional groups from outside the Eurasian sphere. Before I talk about this, let me just clarify for some people who are not aware. Myths do not represent perceived historical events, they do not “happen” at some point in time and have not “happened”, but are “happening” all the time. They are timeless representations of the nature of our world, of ourselves, and of humanity. The meaning behind myths is esoteric, if a certain element of a myth seems to contradict another element it is likely that these two elements are not representations of the same thing or that there is a deeper reality behind these ostensible contradictions.

The Ancient Religions of Eurasia

Indo-European Religion

Let’s start off with the ones with which we are most familiar, the Indo-Europeans. The Indo-Europeans adopt both the classic dragon-slaying myth, and a more distinctive myth known as the War of the Foundation. Both be seen in the form of Vritra, the serpent-enemy of Indra who hordes water from the world. Indra, in slaying the terrible beast, is able to fill the rivers of the world. Vritra is also the leader of the evil band of Asuras known as the Danavas, who descend from the primordial water goddess Danu (not the Irish one).

The waters are a reoccurring motif representing unqualified matter not just in Indo-European mythology but around the world. Water is shapeless without some sort of container, and without containment quickly collapses into formlessness (relatively speaking). Water also surrounds our world, it shapes everything outside of its grasp. Water is also dark, it distorts and obscures what is beneath it. Water in the sky takes the form of clouds. When it is in between the sky and the earth it takes the form of fog, or mist. Indra, by releasing the waters, is able to both characterize the natural form of the world and is able to bring life to the world. From the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rig Veda:

“There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

Neither the realm of space, nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?

There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That One breathed, windless, by its own impulse;

Other than that there was nothing beyond.

Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That One by force of heat came into being”

You’ll notice here that water, the substance which Indra releases onto the world by defeating the primordial enemy of the gods (Vritra) and his race (the Danavas), is characterized as the indistinct substance of the universe, sort of similar to the cosmology of Thales of Miletus, the first Greek philosopher. Thales had pretty similar reasons for (likely metaphorically) describing the substance of the universe as water-like. The serpent-slaying myth is often related to some sort of primeval chaos as well in Indo-European mythology, but I think it is often intertwined with the more characteristic archetype of the “antigods”. In Germanic mythology, this takes the form of the malevolent Jotunn, who descend from the primordial Jotunn called Ymir (as opposed to the gods, who descend from Búri). Contrary to how the dragon Vritra is slain to let out the waters of the world, Ymir’s corpse is actually described as the physical substance of the world. So the Jotunn, in some sense, represent the hyle while the gods represent morphe, they are the intellectual beings forming the body of Ymir into the good world.

“Ganglere asked: How could these keep peace with Ymer, or who was the stronger? Then answered Har: The sons of Bor slew the giant Ymer, but when he fell, there flowed so much blood from his wounds that they drowned therein the whole race of frost−giants; excepting one, who escaped with his household. Him the giants call Bergelmer. He and his wife went on board his ark and saved themselves in it […] Then said Ganglere: What was done then by the sons of Bor, since you believe that they were gods? Answered Har: About that there is not a little to be said. They took the body of Ymer, carried it into the midst of Ginungagap and made of him the earth. Of his blood they made the seas and lakes; of his flesh the earth was made, but of his bones the rocks; of his teath and jaws, and of the bones that were broken, they made stones and pebbles. Jafnhar remarked: Of the blood that flowed from the wounds, and was free they made the ocean; they fastened the earth together and around it they laid this ocean in a ring without, and it must seem to most men impossible to cross it.”

—Prose Edda

Norse poetry, like the previously quoted Nasadiya Sukta, also espouses the origin of the world in an ineffable, qualitatively empty substance which we might recongize as “Chaos”. The Norse called it Ginnungagap, a vast pit surrounded by an icy rime. I guess this makes sense in the frigid north, where water does not naturally settle into a formless puddle but instead freezes up into tense ice.

“When Ymir lived long ago

Was no sand or sea, no surging waves.

Nowhere was there earth nor heaven above.

But a grinning gap and grass nowhere.”

To the Iranics, things are a little bit obscured because all evidence points to a harsh religious schism being formative in the Zoroastrian religion, but I tend to believe that Zoroastrianism is more Indo-European than people give it credit for. There is no denying though, that as time went on Zoroastrians began to incorporate certain deities of other Indo-Iranic peoples into their cast of Daevas, or deities not worthy of worship, and it is likely that the position of “deity not worthy of worship” and “antigod” became assimilated into each other. The Azhdahas, a race of dragons, may represent the earliest clearly defined antigods, as they are later associated with the chief antigod Ahriman. Once again, we run into some ambiguity when discussing Ahriman, who is described as the “twin spirit” of Ahura Mazda. Ahriman is not created by Ahura Mazda, his existence is never explained as a product of Ahura Mazda, it is implied that they have existed together before the beginning of the universe, which led to the philosophical notion of Zurvanism arising in Sassanid Persia. However, I suspect that the notion of Zurvan existed earlier based on the records of classical Greek author Eudemus of Rhodes, which only survive in a paraphrasing by the early medieval scholar Damascius:1

“As for the Magi and the entire Iranian race, as Eudemus writes about this, some of them call the intelligible and unified universe Space (Topos), and others call it Time (Chronos), from which are differentiated either a good deity or a bad demon, or light and darkness before these, as some say. And they then themselves posit the twofold differentiated rank of the superiors after the undifferentiated nature, one leader of which is Horomasda, and the other of which is Areimanios”

We’ll get back to Eudemus in a bit, by the way. But anyways, Ahura Mazda is clearly akin to the position of the Sky Father in other Indo-European mythology, especially the figures of Southern European traditions like Zeus, Jove, and Zojz who roll together the characteristics of Dyeus Pater and the thunder-god Perkwunos (who may have been two epithets of the same deity originally). He has the epithets of the sky-father and is mapped onto the sky-father figure in other Indo-European religions like Hellenism. Ahura Mazda is also not some sort of aloof being floating around in the realm of ideals, he is the creative force in this world and cares about the victory of goodness in this world, while Ahriman is a destructive or more accurately decadent force who is associated with death, decay, and disorder. Plutarch identifies Ahriman with the Greek figure Typhon, who I will get to later. Other traditions which claim Zoroastrian heritage such as the Chaldean Oracles and the Mithraic Cult also operate on an ultimately monistic chasse, so I think it is quite reasonable to say that Zoroastrianism did have an esoteric monistic core. The four elements of Zurvan are said to be space, time, and vata-vayu (who represents the provisionally dualistic nature of the world).

The Zoroastrian approach to theodicy also emphasizes the creation of the physical world as an attack against this evil force, a sort of defensive invasion against Ahriman by Ahura Mazda, which I find quite interesting. This is explained in the Doubt-Dispelling Book of Mardan-Farrukh. This book is also sort of an interesting argument for Dualism — I think it’s misguided, but it’s still quite interesting nonetheless. It identifies Ahura Mazda and Ahriman with the very nature of opposition, they are what make difference by absolute opposition possible. It was written well after the period where monistic theory peaked in Zoroastrianism, by a time where many religions had come and gone, so it’s not surprising that it is Dualistic.

There is a very similar motif to Zoroastrian dualism found in Slavic mythology, and as I’ll get into later, in Siberia as well. Chernobog and Belobog, two gods reported to have been believed in by the West Slavs. Chernobog is good, Belobog is evil. I’m not sure if these are representative of much, as I believe Zoroastrianism was much more prominent among the East Iranic peoples such as the Scythians and Alans than people give it credit for. So it may have been Iranic influence in Eastern Europe as it is not reflected in the myths of all Slavs. Polish Sarmatism round 2 perhaps? I digress. It is not described in enough detail to know much at all.

Anyways… Eudemus also talks a lot about Orphism, and about Homer, which is relevant when we’re talking about Greece. Orphism is one of the most ancient religious movements of ancient Greece, and Proclus describes Orphic texts as a core foundation of Greek religion, but it is also sort of a reformation of the older Dionysian cult, and seems to take things in a more ascetic path in some respects but still recognizes rite and initiation as the object of religious focus. The Orphics viewed the universe as originating from a cosmic egg, which is slightly different but similar to the traditional notion of Chaos, and from it emerge the being Phanes, who is equated with all sorts of different figures including Eros, Ouranos, Aion, and Metis. Along with Phanes comes Ananke or sometimes Nyx, but Phanes is famously absorbed in the form of Metis by Zeus, who through his holding of the office of Ouranos and Kronos, through sharing the demiurgic essence with his brothers Poseidon and Pluto, and through his consumption of his first wife Metis and subsequently absorbing the position of Phanes, unifies several elements of creation within himself.

“Thus mighty Zeus engulfed and swallowed Erikapaios [Phanes], employing all of His power, and drew everything that existed into the hollow of His belly. And now all things in Zeus were created anew, the sky, the sea, the earth, and all the blessed and immortal Gods and Goddesses, all that was then and all that will be, all mingled in the belly of Zeus.”

Side note: Can you think of certain Odinic myths which this reminds you of?

This tradition of Zeus as the essential demiurge, and Ananke as a sort of counterpart to this, is continued in Platonic writings, but the role of Ananke (necessity) I believe shares its hypostasis with three different gods depending on the myth. First, is Gaia, and she plays this part most strongly in Hesiod’s Theogony. Gaia is the first being to come out of Chaos, and through her defined existence subsequently causes Ouranos (heaven) to come into existence. and it is only through the children they produce together that Gaia is covered in mountains, oceans, and all sorts of other things. However, Gaia also creates hideous beings, the Cyclopes and the Hecatoncheires, which Hesiod shows some sympathy to and eventually mentions as assisting the Olympians, but it is possible that earlier traditions do not have such a popular opinion of them. Anyone who has read the Odyssey knows that Homer describes them as children of Poseidon, not Ouranos, and describes them in all sorts of negative ways. They do not care for Xenia, they are full of hubris, they are lazy and don’t work the plow. Also, in the lost Titanomachia, the Hecatoncheires (or at least one who is mentioned) is actually on the side of the Titans. Anyways, Gaia hates Ouranos for his lustiness and helps Cronus (who Hesiod, by the way, describes in very negative terms) castrate him. Gaia also plays some role in helping young Zeus, but her twisted and monstrous children soon become a problem for the Olympians. The Giants, the product of Ouranos’s blood unwillingly falling onto Gaia, seek to usurp the Olympians. Not only are they defeated by the gods but by human heroes, namely Heracles. Gaia is also the source of the most famous monsters of Greek mythology. Directly, she is the mother of the Python which Apollo slays, and the terrible usurper Typhon who can be seen as something of the archnemesis of Zeus, the anti-Zeus even moreso than someone like Cronus. And among the descendants of Typhon in union with Echidna are the Nemean Lion and the Lernaean Hydra, who Hercules slays. The Titans themselves can be considered somewhat “Gigantic”, their direct descent from Gaia is relevant and Hesiod even refers to it in epithets. The Orphics also characterize the material world as “Titanic”, a combination of the divine soul of the dying god Zagreus with the ash-stricken bodies of the Titans who were smote by Zeus’s thunderbolt. The titan Kronos, in some sense, is associated with the temporal. He “eats his own children” in the same way that time consumes everything it produces. This is distinct from Chronos or Aion, who represent eternity. Zeus’s victory over Kronos is the victory of the timeless over the temporal. But what is mainly important is the Giants and the monsters, they are the representations of the chaotic and destructive elements of the world and it is through the Olympians, but also through human heroes like Heracles, that they are destroyed and from the spoils of these conflicts the world is formed. Ex: The temple of Apollo being built atop the fumes of the rotting Python.

Secondly, there is Nyx, who is sometimes equated with Ananke. This makes some sense. Homer says Nyx is a god who even Zeus is hesitant to quarrel with (which would suggest that they are twain spirits, equal in eminence with respect to The One). Hesiod ascribes a cavalcade of negative spirits to the womb of Nyx, as well as the Moirai (the fates) who are also associated with Ananke. Thirdly, there is Hera, Zeus’s wife. This one is much more related to the human aspect of the world. Hera imbues people with madness, with irrationality, most famously with Hercules, while Zeus is associated with justice and rational thought. The union of Zeus and Hera represents the union of the Intellectual Demiurge with the anima, according to Proclus. If you don’t want to believe Proclus because he is so detached from old Greek religion, so be it, but I think the fact that Plutarch basically adopts the same worldview and was also a literal priest to Apollo makes it more reasonable. Plus, it’s a very common motif in Indo-European mythology, the Sky Father and his Earth Mother uniting to create the world. I don’t believe that Gaia and Ouranos can be directly connected to other figures like this in IE mythology, but maybe they can. I have been talking about the Greks a bit too long now.

Now, enough talk, maybe let’s discuss practice. Like I said earlier, I don’t feel that traditional pagan religions were particularly ascetic. Priests, for example, were not just not abstinent but were sometimes even required to be married (ex: the Roman Flamens). In legends, people are not achieving godhood through self-rejection, but through heroism. The Greek heroes seek immortality through glory in battle, or later on at the games or through arete in other areas of life. Stories often discuss warriors and heroes becoming gods, because they do as the gods do. The Romans were a similar way, deifying important emperors and statesmen, although the Romans had a stronger emphasis on pietas, or social duty. This process of mimicking the gods is also the justification for religious rite, which Iamblichus justifies philosophically in his explanation of Theurgy. This attitude is not limited to the Greeks. The Zoroastrians were quite well known for being anti-monastic, because they believed such behavior was shirking duty in life. Likewise, among the Norse, it is the courageous warriors who enter Valhalla and will fight in the final battle during Ragnarok. If you would like to believe that the religious elite was always ascetic and this was just smoke and mirrors for the masses, go ahead. But I don’t see much evidence for it.

The Oath, like I said earlier in a more general context, can be thought of as the atomic unit of Indo-European moral standard. The oath is the most basic truth, so long as it is not broken. Many gods, like Mithras and Dius Fidius, exist primarily with respect to oaths, and many myths involve divine or magical punishment befitting those who break oaths. To the Norse, those who broke oaths (including adulterers) were sent to Náströnd after they died, where they would be gnawed on for eternity by the primeval dragon Nidhogg (almost like there is a connection between these two things…) and similar things happened in Etruscan and Roman mythology.

Also, proper treatment towards guests by hosts, and towards hosts by guests, is one of the first moral standards you hear about any Indo-European religion. I feel like it is so ubiquitous that I need not talk about it too long as I already have so much to say about the Indo-Europeans that it could be its own post.

Egyptian and Semitic Religion

The religious traditions I am probably second most informed on, is the Afro-Asiatic religions of the ancient Near East. I think everyone has some familiarity due to their influence and passing mentions in the Hebrew Bible. Similar to many Indo-European cultures, the peoples of the near east have a regular series of myths involving the Chaoskampf. In the Bible this takes the form of Jehovah against Leviathan, the serpent who swims in tehom, the abyssal waters which surround the firmament. This is a particular word used in the Bible apart from other terms for bodies of water, appears to be either not created by Jehovah, or created by Jehovah before the creation of the world. I don’t believe it is ever specifically stated in canonical scripture that Leviathan swam in the deep, but it is stated in the Book of Enoch. The serpent, I suppose, is an apt symbol for the chaos, because it winds around the world. Jormungandr is the same way. It is not the chaos itself, which cannot really be comprehended, it doesn’t have qualities. It is the idea of nonbeing, while the demiurge at its highest abstraction could be considered the idea of being. The absolute as viewed subjectively. The serpent merely acts as a border between the chaos and the intelligible world.

Leviathan is believed to be etymologically related to the serpent Lotan, who is defeated by the storm god Ba’al in the mythical cycle with his namesake. However, I think this mythical cycle is really sort of its own thing despite its centering around a conflict between Ba’al and a sea god.

The Enuma Elish, a Babylonian poem, is honestly perhaps the best and most succinct example of the classic Chaoskampf myth. It is short, it’s only maybe a dozen or two dozen pages total, so I suggest if any of you are interested in Near Eastern mythology, you read it. The first tablet of the text revolves around the creation of the world, from two different primordial water deities mixing:

“When on high the heaven had not been named,

Firm ground below had not been called by name,

Naught but primordial Apsu, their begetter,

Tiamat, she who bore them all, Their waters commingling as a single body;

No reed hut had been matted, no marsh land had appeared,

When no gods whatever had been brought into being,

Uncalled by name, their destinies undetermined—

Then it was that the gods were formed within them.

From what I can understand, Apsu is representative of freshwater while Tiamat (who is more important for what we’re getting at) is representative of saltwater or the ocean. Anyways, heaven (Anu) bubbles up from the deep creating heaven, and too comes Enki, who upon hearing word that Apsu plans to destroy the gods, slays Apsu and makes his dwelling place from his body.

Then, Tiamat seeks revenge against the gods. Tiamat, who is sometimes a female goddess, and sometimes a serpent, or a goddess who had in her control serpents. She assembles an army of beasts and attracts some souls to her cause, but is ultimately defeated by the champion of the gods, Marduk. After defeating Tiamat in an epic battle, he uses her remains to construct the sky and the world below. Mankind, however, is formed with divine blood. Marduk becomes the king of the gods henceforth.

Now that I have already gone about explaining the significance of the waters, the serpents, the antigods, in my section about the Indo-Europeans, I’m sure you can recognize the meanings here. The world is substantially comprised of chaos, but divinely ordered and in a sense “restored” by this presence of form. Not only that, but the act is allegorically represented as a heroic act, egging on heroes in the real world to mimic such behavior.

Proclus has a pretty interesting, albeit somewhat flimsy claim about Semitic theology, which reflects many of the ideas found in the Platonic tradition:

“[The Chaldeans] call it by a name of their own, ‘Ad’, which is their word for ‘one’; so it is translated by people who know their language. And they duplicate them in order to name the demiurgic intellect of the world, which they call ‘Adad, worthy of all praise.’ They do not say that it comes immediately next to the One, but only that it is comparable to the One by way of proportion: for as that intellect is to the intelligible, so the One is to the whole invisible world, and for that reason the latter is simply called ‘Ad,’ but the other which duplicates it is called Adad.”

Obviously, Proclus is referring to the storm-warrior-god Hadad who participates in his own dragon slaying myths and is equated to Marduk. The etymology seems to be contrived, but he isn’t the first source to say this about Hadad/Adad. So it is possible that it was a folk etymology based on the perceived attributes of Hadad.

Among the Egyptians, who are revered in antiquity as having one of the oldest and wisest religions (which was unfortunately reduced heavily in complexity following the Ptolemaic ascendancy), similar myths are present. Like Anu, the earliest god of the Egyptians, Atum, rises from the abyssal waters of Nun. Egyptian religion seems to have its own sort of “trimurti” similar to the Hindoos. Atum represents pre-existence or post-existence, pure potentiality. Ra, the primary sun-god, is associated with existence. And Khepri is associated with the act of creation, the coming-to-be. For these reasons, Khepri is seen as the rising sun, Ra as the midday sun, and Atum as the setting sun. Both Atum and Ra are associated with a battle against the chaotic serpent Apep, who either arose from the primordial waters or from the umbilical cord of Marduk, once again representing the duality (of course, a mere contingent duality compared to the underlying unity) of these beings. Apep is the “residue” of creation, and a mere symbol for the unimaginable, unintelligible substance of Isfet. Maat, the daughter of Ra, is associated with the cosmic order. Ra, with some of his allies, eventually go and slay the serpent in a variety of myths, although there is also iconography that depicts Atum as defeating or battling Apep.

The Egyptian tradition remained highly important among esoteric crowds in the Hellenistic world and even to modern Traditionalists, but may have collapsed into superstition for the general public due to a Greek takeover of the elite. It likely had a large influence on the Hermetics. Anyways, Egyptians also seem to emphasize good action and adherence to rite in this world as a path to goodness in the afterlife. Asceticism had a place in Egyptian religion only insofar as an ascetic lifestyle pertained to the notion of avoiding ritual uncleanliness. Famously, the Egyptians were known for deifying their Pharaohs, just like the Romans did with their own rulers. These Pharaohs can be considered ideal men, who use their immense power to order the world adhering to divine will.

As far as the nature of Oaths and Hospitality go, the Hebrew Bible upholds both as very important. “Using the lords name in vain” actually refers to swearing a vacuous oath to God, it doesn’t mean saying “Oh my God” or “God Damnit”. Not sure why we were taught that as kids. Very similar to other belief systems I have discussed where certain deities were viewed as omniscient protectors of oaths. The Egyptians were the same way, often making contracts or agreements in temples where to make a vacuous oath in the presence of a god would be considered particularly impious. The Biblical description of hospitality is also very similar to what is seen in other religions:

“Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it.” — Hebrews 13:2

There are very similar myths in Norse and Greek mythology. Odin often takes the form of a wanderer, who travels to people’s houses and tests their hospitality. Greek mythology has similar myths, for example Baucis and Philemon, who despite their poverty were the only worthies in Tyana who behaved hospitably towards the disguised Zeus and Hermes. Another example is Odysseus’s return home disguised as an old man, who is treated hospitably by Odysseus’s old Swineherd, and treated poorly by the Suitors. The value of hospitality was similarly important among other semitic peoples, in fact it’s actually part of Hammurabi’s Code to provide proper hospitality to visitors.

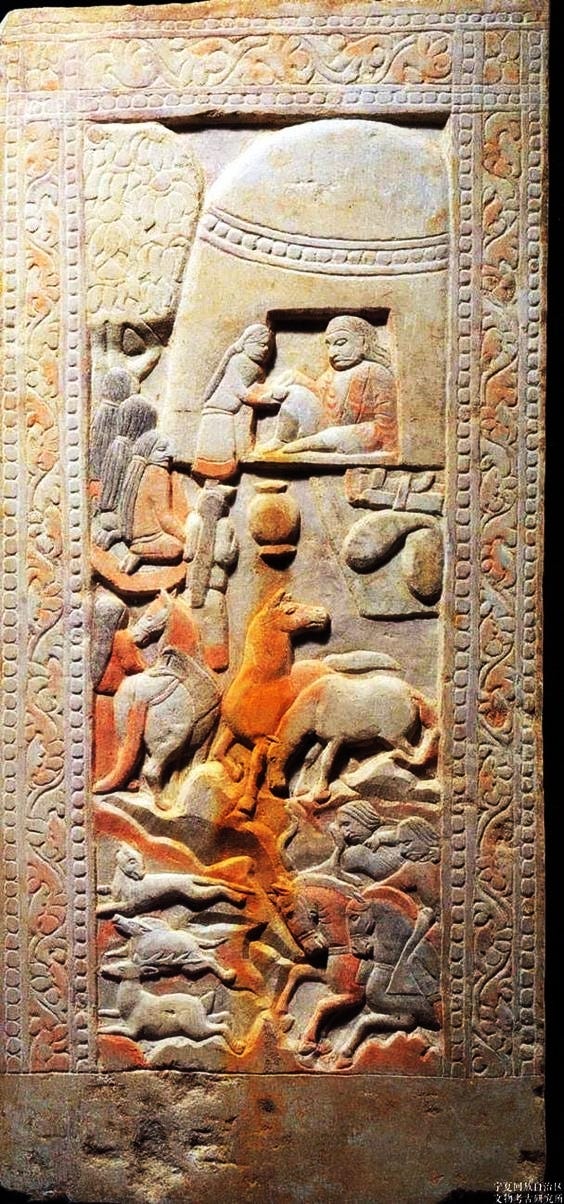

Altaic Religious Tradition (Tengrism)

Now, first of all, let me clarify that there probably isn’t an actual Altaic language family. What was once thought of as a language family is most likely a Sprachbund of unrelated languages. But it seems either way, these cultures — Turks, Mongols, and Tungusics, all had a profound impact on each other, especially in terms of religion. Mongols and Turks historically practiced a religion that became known as Tengrism. Tengrism revolves around the worship of the Tngri, the gods and spirits, with a particular emphasis on the highest Tngri Gok Tengri and Kok Tengri. Gok Tengri is entirely abstract and all-encompassing, and can be considered as being the ultimate reality. Kok Tengri is the blue sky above us, the lord of the heavens. Kok Tengri can be considered as the intellect, our “subjective absolute”, while Gok Tengri can be considered as the Monad, the ineffable objective absolute. Gok Tengri cannot truly be personified or visualized for this reason. In some myths, the two deities who take these respective roles are Ulgen and Kayra, it really depends on the source.

Unfortunately, there aren’t a great deal of records from Turks until the middle ages, postdating our other sources and dating to after a time of various outside influences.

There are different creation myths in Tengrism. One of them involves the comingling of Kok Tengri, the sky, with the dark earth, which is a motif we see in Indo-European mythology as well and which fits the motif we have been constructing. There is not all that much difference, insofar as the referent behind these things. Slaying a dragon, seducing a woman… I don’t think I am crazy for saying they are that different, because both represent the submission of chaotic substance to solar order. Keep in mind, these are patriarchal bridenapping cultures. Other myths involve a primordial ocean personified as Ak Ana, with Tengri being represented as a white goose who glides over the waters not dissimilar to how Jehovah is described in the Bible. From these waters, the earth is fetched from the sand and formed. This myth is also present in some Eastern European folktales, so it’s not clear if it came to them from Turks/Uralics or the vice versa, but I would think the former is more likely because it isn’t seen in other Indo-European myths. However, the waters are also described as “time” which could mean that the waters simply represent an internal quality of Gok Tengri, with the goose representing another quality. After all, the behavior of the goose in these myths determines the flow of the water. In his loneliness, he creates Ulgen and Erlik. Ulgen is our creative demiurge who upholds cosmic order, he is the protector of humanity and the creator of the world, and is associated with the Axis Mundi. Erlik can be seen as more of a Satanic or Ahrimanic figure, he is associated with death and decay and the underworld and is generally considered evil, albeit perhaps a necessary evil for the existence of the ordered world (hence why people are willing to sacrifice to Erlik).

The Turco-Mongolic peoples have long worshipped their ancestors and their heroes, like the Indo-Europeans. Genghis Khan has historically been worshipped in the manner of a god in Mongolia, and you can still visit his tomb. It’s a little bit hard to get a grasp on what Shamanic cultures really believe in terms of some sort of soteriology, because they already have such an integrated view of the physical world with the spiritual world. While heroic figures may be deified like the Great Khan, I don’t think the idea of “Salvation” was as necessary when you already believe (I think, with good evidence) that your local Shaman could travel to the 12th level of Heaven using spirit travel and still chooses to return to earth to inform you and engage in ritual. Perhaps read this Gildhelm article to further understand the extreme, almost blissfully aloof nature of pre-civilizational religions which Tengrism seems to partly belong to (remember that many Tengrist traditions don’t come to us today from the high civilizations of the Turks, but from Siberian tribal peoples). Although, perhaps I am simply ignorant of Tengrist beliefs, and they actually do have a complex soteriology and eschatology. I also know nothing of Tengrist attitudes towards hospitality, but I know that many Turkic and Mongolic tribes today are extremely hospitable. If you are a foreigner and travel to them, they will demonstrate their hospitality and maybe even offer you their daughter’s hand in marriage. That is how hospitable they can be sometimes. Also, I heard that some tribes in Siberia do not eat vegetables… They say they taste like wood… I would like to go to these places because I am also anti-vegetable and believe they are toxic…

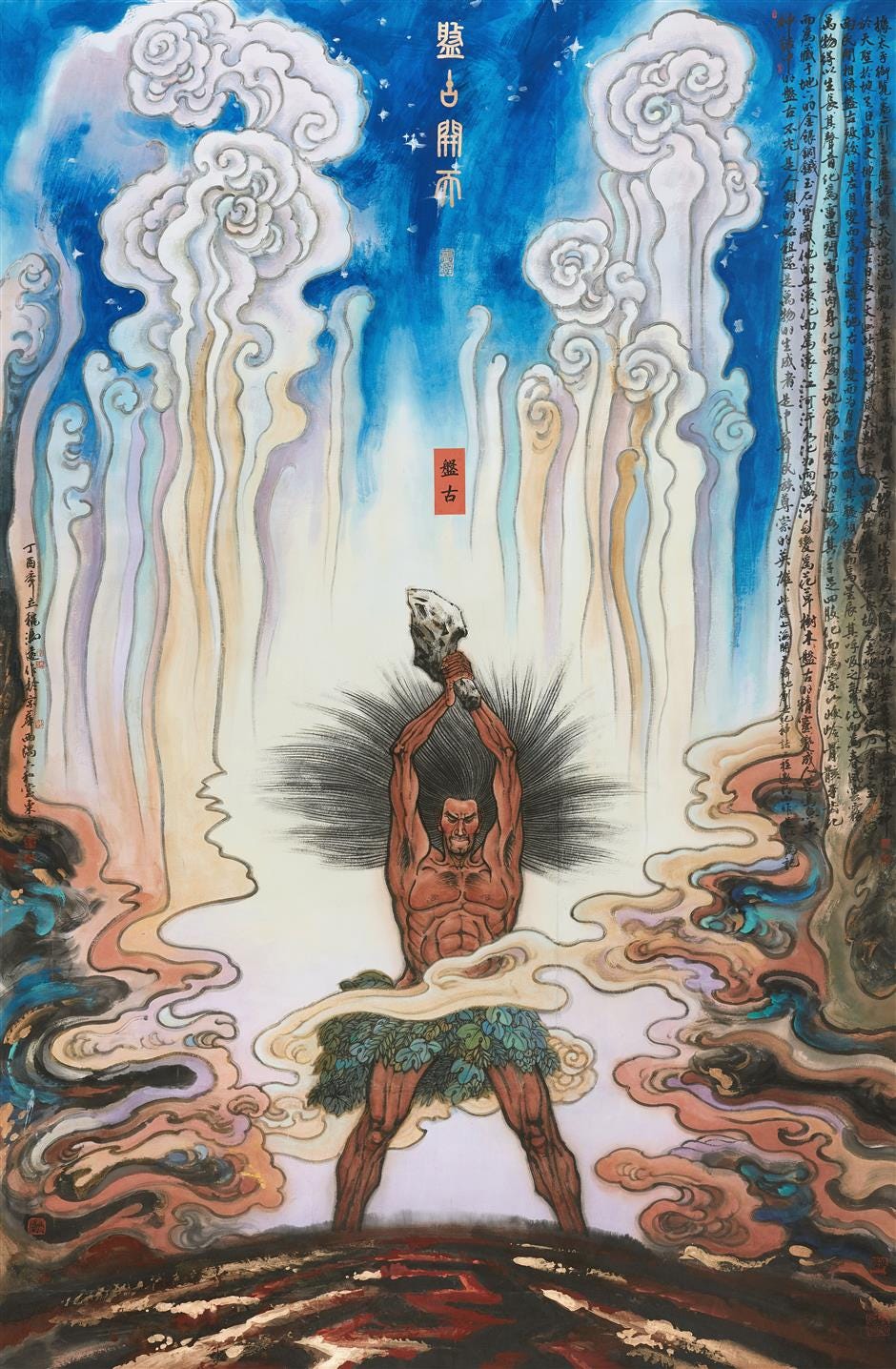

Chinese Folk Religion

The Chinese, as I have said before, are a little bit different from Westerners in their “mode of civilization”, and I have heard some suspect that the Chinese are naturally atheistic. Not in the sense that they don’t naturally believe in god, but that they just don’t care about religious literature that much. This would explain a relative dearth in mythological literature from early China, so much so that pretty much all Chinese mythological literature relating to the creation of the world is heavily tied into Taoism or Confucianism and comes from middle or late antiquity onwards. This is not a problem of obscurity like the Turks or the Norse, as the Chinese were just as advanced in record-keeping as the Semitic and Aryan peoples. Chinese religion has long been focused on ancestor veneration primarily, with a less significant focus on what is known as Heaven Worship not dissimilar to what the Turkic peoples do. However, all strains of Chinese folk religion are heavily influenced by Confucian literature, and to a lesser but still significant extent, Taoism. Chinese cosmogony tends to begin with the notion of the Yin-Yang, or the Cosmic Egg, both of which speak to an underlying unity which expresses itself through provisional multiplicity (what the Hindoos describe as Vishishtadvaita). The prince Liu An records this creation myth in his compendium of courtly dialogues about the Chinese schools of philosophy:

“When Heaven and Earth were yet unformed, all was ascending and flying, diving and delving. Thus it was called the Grand Inception. The Grand Inception produced the Nebulous Void. The Nebulous Void produced space-time, space-time produced the original qi. A boundary [divided] the original qi. That which was pure and bright spread out to form Heaven; that which was heavy and turbid congealed to form Earth. It is easy for that which is pure and subtle to converge but difficult for the heavy and turbid to congeal. Therefore, Hell was completed first; Earth was fixed afterward. The conjoined essences of Heaven and Earth produced yin and yang. The supersessive essences of yin and yang caused the four seasons. The scattered essences of the four seasons created the myriad things. The hot qi of accumulated yang produced fire; the essence of fiery qi became the sun. The cold qi of accumulated yin produced water; the essence of watery qi became the moon. The overflowing qi of the essences of the sun and the moon made the stars and planets. To Heaven belong the sun, moon, stars, and planets; to Earth belong waters and floods, dust and soil.”

—Huainanzi

The Chinese have always worshipped heaven both as a deity and a concept, and it is this deity — Shangdi — that is responsible for the ordering of the universe. This concept in China is known as zàohuà, or “creation-transformation”. huà is distinct from zào (creation) insofar as huà simply involves the shaping of preexistent things. In the Shang dynasty, the full nature and will of the world (Di) was divided into Shangdi (the lord of heaven) and Xiadi (the lord of earth), the latter of which was more often associated with the negative attributes of the world and most interestingly with the foreign enemies of the Chinese. However, both are united in the overarching willpower known as Di. Di is perhaps closest to the later notion of Tian, who like the Platonic Monad is both immanent and transcendent. Heaven (Shangdi) manifests itself in all things through li and its emanation, chi (yes, the same stuff in Dragon Ball Z which allows Goku to use the Kamehameha), which can roughly be equated to the Platonic concepts of form and soul (anima). Just as Plutarch described the intellect as leading the soul (psyche) to goodness, and just as Plato describes Zeus using persuasion to lead Ananke to goodness, li brings qi to goodness. Everything, even inanimate objects, contain within them these things. Shangdi, like Ulgen, is associated with the Axis Mundi and the vertical chain of being, from the Monad all the way down to particulars, which should bring inspiration to us over horizontal sets of beings (load bearing ‘s’). Plz read long essay of

perhaps to understand this, okay?According to the Confucians like Zhu Xi, who albeit are ideologically motivated, human beings on earth continue the work of Shangdi by bring order to earth and participating in their own sort of zàohuà, and it is due to this process of microcosmic creation that the ancestors are worshipped, and why certain great emperors, scholars, writers, and generals may ascend to the position of godliness through proper creative behavior in life, although as I talked about in my China post, the Chinese don’t have a culture heavily focused on hero veneration. The greatest semi-mythical emperors, such as Yu the Engineer, are lauded for their statecraft and agricultural innovations, and less so any feats of battle. But it’s still the same idea, ultimately. Their greatness comes from correct action in the world, which makes this world good. The Confucians refer to this as gōng.

The social hierarchy is recognized as harmonious, and is connected to the filial heirarchy. So adherence to one’s social role is good action. Similar to what the Hindoos believe, or at least used to believe before the undercaste finished its long demographic march into the elite in that accursed subcontinent. See my India post!

Another popular creation myth, also influenced by Taoism, is that of Pangu, a cosmic man similar to the Vedic Purusha. I thought I would mention this one, because it’s what people usually bring up when discussing Chinese creation myths. Purusha, in my opinion, represents a reconciliation between the creator and the creation, both Pangu and Purusha are self-sacrificial beings whose bodies comprise the whole of existence, while in other stories one primordial element acts upon or synthesizes with another (as seen in the above story). Pangu particularly, is described as splitting apart heaven and earth, the two primordial substances which arise from the chaotic cosmic egg. The Pangu myth is not recorded until the middle ages, but is said to be very old. The story goes that at first, there was simply a cosmic egg, which Pangu resides in. Pangu separates the celestial heavens, the light shell of the egg, from the heavy and opaque earth, and holds them in differentiation for 18,000 years, and then he dies and his body qualifies the earth. His body becomes the mountains, the rivers, the rain, the sun and moon.

These myths also influenced Korean mythology, but the Koreans are not a serious people so I will not speak anymore of them. Do not pay attention to the Koreans, they are not a serious people, they are nobodies. Perhaps once they were somewhat like the noble Mongol, thousands of years ago, but they have been contorted into half-rate Chinamen through Confucian influence, and honestly the entire peninsula belongs to its original inhabitants, the Japanese. The Koreans are Yayoi who speak a Siberian(?) language and practice Chinese religion. Their neighbors also call them effeminate and annoying.

I do not have much to say with regards to Chinese views towards hospitality and oaths. I don’t know if the Chinese are a hospitable people, I’ve never been there and they are kind of cold. Also, just to clarify, I am using China as a demonstration of the entire Sino-Tibetan tradition because (again, as I discussed in my post on China) the Chinese are really the most pure and true descendant culture of that whole group, staying in the very same region as their ancestors.

Shinto Theology in Japan

Oi oi oi! Baka… Finally we get to ANIME WORLD… DATTEBAYO!!!!

Ehh, no… But seriously, Shintoism is one of the best religions around I think. I would actually call myself a Shintoist, if it wasn’t for the obvious stereotype that would surround a White person who calls themselves “Shinto”. Like other Pagan religions, Shintoists believe that other gods are simply foreign emanations of the Kami, so this would not at all involve the worshipping of Japanese gods. However, there have been Japanese people who have believed in spreading Shinto worldwide, with this caveat. And they have believed, like the Zoroastrians and the Jews, that the Japanese were the chosen people. Shinto is perhaps the last descendant in this world of proper unadulterated Paganism, or at least it was before 1945 when the U.S. forced it to be crippled. This is both due to the Japanese state’s historical persecution of Christianity and other outside forces (they would actually go as far as to kill anyone who shipwrecked on their island) and also the early-modern movement to differentiate Shinto as a distinct tradition from the islands Buddhist schools. Today, sadly, Shinto is a shell of its former self. Outside of a minority of devotees and the priesthood, it is more of a cultural ritual which doesn’t tickle people’s religious curiosity. It is criticized by the Left for its “outdated” and “superstitious” rituals and its association with Imperial Japan and general social conservatism, meanwhile the Japanese right associates itself increasingly with rats like the Unification Church. I’m pro Shinzo Abe, but the guy who shot him at least had a justified reason not to like Abe in being anti-UC. The Japanese slaughtered unrepentant Catholics by the dozens during the Tokugawa Shogunate, but ally themselves with these cultish clowns who seek to subvert Japanese traditional religion? Okay, enough jibber jabber, I’m getting off topic.

The Japanese are a little bit unique, in that their big solar deity of choice is the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, who likely rose to prominence through a similar series of events as what happened with Sol Invictus in the Roman Empire (read or listen to my Substack on that, by the way. Praise the sun!). Basically, the Imperial lineage (the Yamato Clan) claimed descent from Amaterasu, and was especially focused on Amaterasu, so over time Amaterasu became a more and more important figure. This is similar to what happened with Aurelian, whose mother was a priestess of Sol. However, Amaterasu is not the creator deity, that honor goes to her father Izanagi.

The story goes — and I hope I’m not getting repetitive at this point (but that’s kind of the whole point) — that at first, there was simply shapeless chaos, from which ascended heaven, and from the residue would arise a primordial ocean. Several generations of gods would be raised up in heaven, and at the last generation, the twins Izanagi and Izanami (who are later associated with Yang and Yin in syncretic models) descend to the waters to create. Izanagi swirls the waters, at which point the land and earth is no more defined than a pool of oil floating in the Gulf of Mexico. From the waters, he creates form, and he breathes life into the world. His sister-wife Izanami tries to provide him with children, but his wife Izanami dies in childbirth as she is burnt by the kami of fire, her last child. Izanagi goes into the underworld to receive her, but when he lights a torch he finds that she has eaten the fruit of death and become a rotting, maggot-ridden corpse. In disgust he flees from the underworld, and his zombified wife in her anger declares that she will destroy his life, but he responds that he will create more life than she can hope to destroy. Izanami is also the lord of the Oni, what we in English would call ogres or demons, who serve as enemies for later Japanese human heroes (and some Kami, not that there is a fine line between the two) to slay. They are very similar in this regard to the Divs/Daevas of the Shahnameh and Avestas.

In one version, Izanagi produces the three greatest gods after ritually bathing to purify himself from the witnessing of his wife’s rotting body. Shinto has a very high emphasis on purity, similar to Zoroastrianism. In another myth, Izanami does not die and become the queen of death but instead produces these children with Izanagi on earth. These children would be Amaterasu, the sun-goddess; Susanoo, the warrior thunderstriking god; and Tsukuyomi, the moon. The former two are ancestral to the first emperor, Jimmu. It’s honestly quite strikingly similar to the Proto-Indo-European pantheon reconstruction. Both in the sense of one of two primordial twin gods becoming the underworld deity, and in the sense of a sky father bearing the sun and moon and a thundering warrior-prince. Susanoo is also a serpent-slayer, like Hercules and Thor, although the myth of Yamata no Orochi is maybe more like Theseus slaying the Minotaur in my opinion. Susanoo’s slaying of Ukemochi (causing crops of the world to spring from her corpse) is maybe more of a classic “creative destruction” style myth.

So, clear parallels to other cosmogonies, but what about Shinto praxis? What about Shinto philosophy towards life and towards salvation? Well, first of all, it is implied in the creation of the world that it is better than it is evil. Like Ahriman and Ahura Mazda, the source of life and death in this world came together, in twain, but the force of creation and purity is able to overpower the force of decadence and pollution ever-so-slightly. Human beings are also intrinsically more good than they are bad, but have a responsibility on earth to avoid impurities and preserve cosmic order (wa or kannagara). All human beings eventually become ancestral kami after they die, but great human beings and particularly the imperial family become greater kami. These individuals are known as Arahitogami, and sometimes they were considered not just human beings who were worthy of being considered great Kami, but were actually viewed as incarnations of a Kami or human beings possessed by Kami in order to shape the world. It is often said that Japanese people are “born Shinto and die Buddhist”, which is a reference to Buddhism’s focus on the afterlife and Shintoism’s focus on life. You can be both, of course, simultaneously, and many people have. Shintoism is much more focused on this world, however, which it does not relegate as an illusory world of suffering, but a good world we should be thankful to have been born into. Some of the most important values in Shintoism are honesty/integrity (shoujiki) and fidelity, just like other Pagan cultures I have discussed, as well as hospitality (Omotenashi).

Uralians

I was going to write about the Uralics, about the epic Incel-demiurge Ilmarinen (who was probably the original king of the Uralic gods, Ukko is an Indo-European sky-father disguised in a reindeer’s pelt), but Uralic mythology just doesn’t have much of a source that is not influenced by Indo-European, Christian, or Tengrist literature. Hungarian pre-Christian religion seems to be influenced quite a lot by Turkic and Iranic religion, with Tengri and Mazda being akin to Isten, and Erlik and Ahriman being akin to Ördög. The Finns obviously had a fairly advanced bardic tradition, allowing for the compilation of the Kalevala and its centering around the bard Vainamoinen, but the Kalevala is very strongly influenced by Germanic and Baltic mythology. Again, I suspect that Ukko is probably Perkūnas and the term Perkele was just an epithet for Ukko before it became an insult in Christian times. It also does not tell us about the creation of the universe, it starts out already having established the sky, his daughter Ilmatar, and the primordial ocean. So… Sorry, Finns. I am not anti-Finnish! I like Finns.

Mesoamerican Religion

The Aztecs had a very bizarre religion, it is deviant but also fascinating. However, it is among the earliest recorded Native American religions and belonged to a high civilization almost on par with those of the Bronze Age Near East. I say almost, because they did not have metallurgy and they did not make good use of the wheel, but they did have a proto-writing system and large cities. So it is worth discussing, even though it is a relative outlier.

There are two senses in which a “comsogony” occurs in Aztec religion. First, there is the ultimate source of divinity, and of all creation. Secondly, there is the creation of the current world. Because, as it is well known, the Aztecs believe that we are on the fifth world to exist, with the previous four having been destroyed. The creation of the earth is described in the Codex Chimalpopoca. Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca descend from heaven into the waters, the aftermath of the end of the Fourth Sun, and fight a giant hermaphroditic sea serpent or crocodile named Cipactli. In the battle, Tezcatlipoca is forced to use his foot as bait, and loses it, but the beast is slain in the end and the earth is created from its remains, similar to the story of Ymir. The loss of Tezcatlipoca’s foot could be considered as an addition of a divine element into the earth, but it’s up for interpretation. Especially because another legend recorded by the Spanish (Gerónimo de Mendieta) tells of another celestial deity, Mixcoatl, creating mankind through the impregnation of this cthonic deity. Perhaps both are true, and it is the celestial seed which represents humanities greater connection to the divine realm than inanimate objects. All the gods descend from Ōmeteōtl, the ultimate and all-encompassing creator, who resides in Ōmeyōcān, the highest heaven. However, from what I read it seems that Cipactli formed within Omeyocan on its own, similar to Ometeotl. It is very hard to find sources on this, it is all old and obscure codices which you have to buy... But Ometeotl could be considered akin to Proclus’s description of Adad as “One One”. The name translates literally to Two-God. It is Teotl, pure divinity, reflected into itself. Kind of like Anui-el from TES… When the fifth sun, Huītzilōpōchtli, takes the mantle, there is a more microcosmic chaoskampf, the endless war between the day and the night. According to the Florentine Codex, Huītzilōpōchtli must constantly fight against the forces of the night, his older siblings the Centzonhuītznāhua, led by their older sister Coyolxāuhqui. They are associated with the stars and the moon. The Aztec warrior-elite, and the Mexica nation in general to a lesser extent, are the chosen of Huītzilōpōchtli, the leaders of his order on earth.

The preceding Maya civilization likely had many similar beliefs. Quetzalcoatl is a local god that was adopted by the invading Uto-Aztecan Nahuas. The myth described earlier is probably from the Mayan myth described in the Popol Vuh. Huracan, the Mayan version of Tezcatlipoca, is the only being in existence along with Qʼuqʼumatz, the Mayan version of Quetzalcoatl. That version doesn’t contain the Chaoskampf though, as far as I know.

Conclusion + on the Axial Age

For any of you who are unaware, the “Axial Age” refers to ~800 BC to ~200 BC, the period where most of the organized religions which came to dominate the medieval and modern world began to emerge. As well as the discipline of philosophy. I have alluded to some figures associated with the Axial Age in this post. Plato, Confucius, the Buddha, Zoroaster, and Laozi (through mentioning Taoism). If you want an overview of the differences between Axial Age religions, which tend to inspire the well-known Perennialists and Traditionalists of history, and Pagan and “Pre-Pagan” animistic religions (Paganism *is* animistic, but is a more intricate form of it), perhaps read this post.

I think a major point against many of the “Trads” that I want to give, is that the actual religious tradition is far more enthusiastic about the world than the Dharmic religions, which don’t necessarily represent a philosophical divergence but more of a divergence in attitudes. It isn’t that they were simply “life accepting” as some people call it, but they really viewed their development on earth as somehow metaphysically significant. This doesn’t mean that the ultimate fulfillment was not awaiting them beyond this world. This actually also extends to some people which in the post I linked are labeled as part of the “transcendentalists”. I don’t think it is fair to call Plato or Confucius or even Zoroaster “transcendental” in the way that Plotinus, the Buddha, and certain Hindus are. Yes, they were reformers, but their reforms had to do with more minor things like what sort of myths should be told about the gods and how society and rite should operate. Even the Buddha, in the Mahayana interpretations places a lot of emphasis on wanting to extend goodness across the world. But in these old traditions, The world was not “illusory” yet, nor was the goal of religion and philosophy “self-immolation” or return to unicity through some sort of renunciation of the world. In fact, the idea that even the Axial Age religions demand this is probably coming from a misinterpretation of what they are saying.

As I wrote this essay I became less and less critical in sentiment towards the classic “Trads” who focus all their energy on Dharmic/Platonic stuffs. First of all, the ideal living I have described in all of these religions is not really that different from Karma Yoga. I think contemplative and active Yoga are the best, while ascetic renunciation hmm I am not so fond of, because in my eyes it is actually just as motivated to reject what comes naturally to you as it is to do what comes naturally to you because you feel entitled to fleeting rewards. Secondly, unification with the godhead is not described correctly through a pessimistic lens. It is not the escape from life, but the escape from death, and the ascension to the state of ultimate power. If you read Mahayana Buddhist literature, achieving Buddhahood is much like reading the end of an obby in Roblox and being able to use all of the hax and gimmicks on the obby map and bother people, like the gravity coil and whatnot. The Buddha could literally fart hurricanes and use the kamehameha. I still prefer the Vishishtadvaita model and believe this is what is closer to the “Tradition” if it exists, which is simply full familiarity and recognition with the godhead and residence in his abode while retaining a separate identity, not very different from the Christian notion of heaven actually. Perhaps it is something akin to what Proclus describes the Gods as, as “henads”. But if you want to fall into that rabbit hole, do it yourself. I still don’t really understand the Henads that well, and so I stick with the idea that the gods reside in the intellectual realm.

Gnosticism as Feminist Esoterica

Now, I also wanted to talk a little bit about Gnosticism, because it essentially suggests the opposite view, that the demiurge is ignorant at best and evil at worst, and “trapped” human beings in these sort of “flesh prisons”, and that all matter is his own creation. And yet, the Gnostics seem to recognize the Demiurge as molding the world nonetheless out of his own creativity and not out of divine inspiration, for he is ignorant of it. Sophia, the bride of Christ and the representation of soul, causes the demiurge to sort of fumble into existence outside of the divine sphere by descending without her partner, Christ. Sophia, in this context, represents the divine spark in human beings while the masculine Demiurge who is responsible for actually forming and designing this world, is the enemy of humanity (either through his own malevolence or through a sort of bumbling ignorance).

This, to me, seems like a sort of bizarro world version of Plutarch’s philosophy, where the intellectual Demiurge is fundamentally good and material is characterized by an evil world-soul which the Demiurge… Umm… Inseminates… With reason. And this turns it good (mostly). This makes some sense, the soul is sort of the animating part of us while the intellect is more static and unchanging.

Nonetheless, the Gnostics were still a pretty patriarchal group, in some sense Sophia is blamed for all of this nonsense with her mistake (Women… Amirite?) but I have noticed in my travels that a lot of Women are drawn to Gnosticism. I have seen it on the right, a lot of women get really into occulty Serrano type stuff (Serrano was a Cathar fanboy). Also, by the way, a lot of these women are trannies like the now disgraced Substacker “Madame Z”. Trannies practice a sort of gnosticism-lite where they hate their bodies and think they were just “accidentally” placed in them. The Platonic crowd recognizes the body much more as an emanation of the soul instead of merely a flesh prison so there are less trannies among them. I have seen Gnosticism also among radfems, who use it to suggest that men are pretty much just the most evil things ever and are Hylics (the opposite is true albeit). It’s such an interesting inversion of the more traditional view, where women’s retardation is sort of seen as a cause of evil (ex: Eve, Pandora). It makes sense, women live kind of tragic lives in this world. They have to watch the thing they love so intensely, their children, grow up and leave them. They are timid and neurotic and fear the coercive and abusive powers of men. They think of the world in terms of emotion, of feeling, rather than in terms of ideas and systems like men. So if you get too far into feminism you end up having to confront the possibility that there are certain elements of womanhood and manhood nature selected for which are so harmful to women that the only option left is to Poon out or to become a world-hating Gnostic. Did you know that 30% of women in the stone age were bridenapped?

I don’t want to rag on Gnostics too much, I’m not really one of those James Lindsay types who blames them for everything. But there is a sort of feminine current running through it, a rebellious daughter mentality. Yaldabaoth is just their dad, they hate that they were accidentally born under his control. Also, when I go on YouTube all of the Hermetic Platonic types as usually very well put together and wordcelly, meanwhile anyone who has Gnostic leanings usually comes off as some sort of insane conspiracy theorist hippie. So there’s that too.

Umm, to end off I will not give a boob break, so I will give this video of grilled lobster tails:

AAAAAAND a woman just appeared in my tiktok ipad screen and annoyed the fuck out of me by making a stupid "debunk" video where she turns from a 2/10 to a 6/10 with copious amounts of makeup while mentioning literal pseudoscience like "Emotional Intelligence" and whining about mansplaining. Jesus fucking christ they annoy the piss out of me I should have spent more time shitting on feminists in this essay

Marking this on my to-read list. Will return