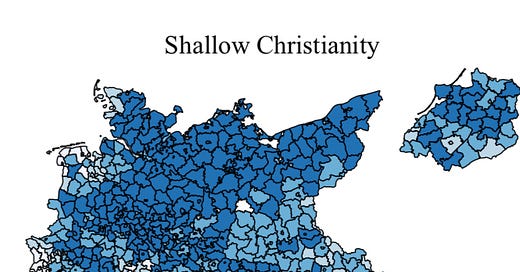

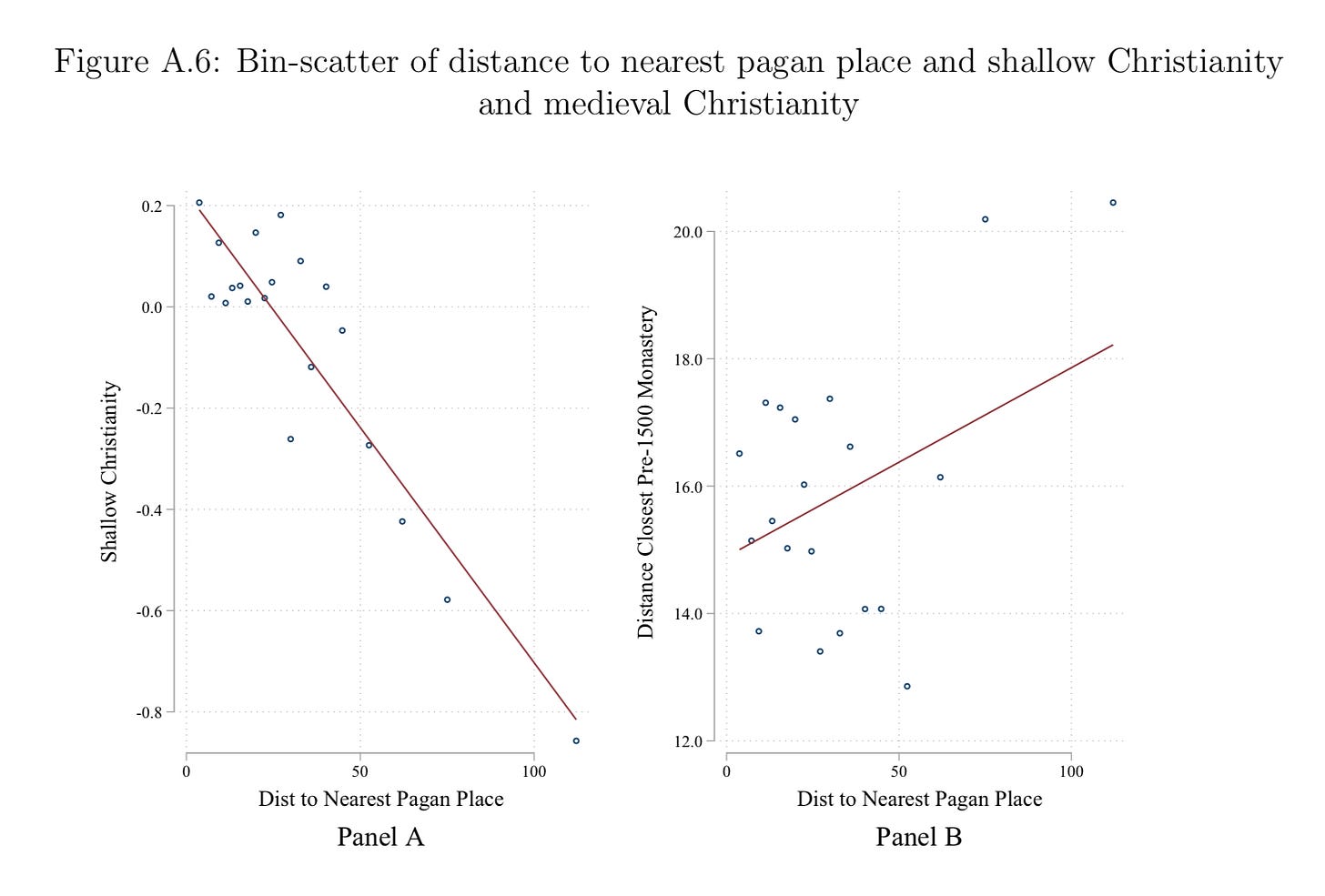

I’ve said before on here that Protestantism is a Judaizing Branch of Christianity. However, the question of why it was so successful in Germany, Scandinavia, and the Low Countries still interests me. There are plenty of common reasons — this region was more individualist, more distant from the center of Church authority, coincidentally closer to Martin Luther and his disciples (which is actually much more significant than you might think), the historical butting of heads between the German nobility and Catholic clergy, et cetera… However, I do wonder if the uniqueness of ancient Germanic religion played a role. But before I explain just how it was unique, let me just clarify that (despite how farfetched it sounds) there is some statistical evidence for this. In this paper, the connection between proximity to Pagan shrines and Christian (pre-1500) monasteries, and so-called “Shallow Christianity” and subsequently Nazism, is studied. Shallow Christianity was determined by prevalence of Christian given names, belief in clairvoyance, and religiosity (which is just a strong negative corollary for belief in clairvoyance), and it basically looks like a map of Protestantism in 1930s Germany. Maybe a little denser around the northern Rhineland, but otherwise very similar.

What you think of the way “Shallow Christianity” was measured is not very relevant, what matters is it can be used as a proxy for Protestantism. And, importantly, there is a significant correlation between Shallow Christianity and proximity to Pagan religious sites. And no, there is not a strong negative correlation between proximity to pagan sites and proximity from Christian sites which could explain this all as proximity to Christian sites discouraging Protestantism (which it did, as is shown elsewhere in the study).

In dealing with Catholicism, there’s no denying that the Roman Pagan religious strata influenced the way the Catholic Church was organized and stylized. The Pontifex Maximus was originally the title of the Roman Emperor, who was the head of the state-sanctioned Roman priesthood. The Roman State ensured that the Priesthood was pretty heavily organized and formalized into a heirarchy, with the College of Pontiffs at the top. However, even in more primitive, related cultures like the Celts, the priesthood was very sophisticated and well-connected. See what Julius Caesar says on it:

“Throughout all Gaul there are two orders of those men who are of any rank and dignity […] But of these two orders, one is that of the Druids, the other that of the knights. The former are engaged in things sacred, conduct the public and the private sacrifices, and interpret all matters of religion. To these a large number of the young men resort for the purpose of instruction, and they [the Druids] are in great honor among them. For they determine respecting almost all controversies, public and private […] Over all these Druids one presides, who possesses supreme authority among them. Upon his death, if any individual among the rest is pre-eminent in dignity, he succeeds; but, if there are many equal, the election is made by the suffrages of the Druids; sometimes they even contend for the presidency with arms. These assemble at a fixed period of the year in a consecrated place in the territories of the Carnutes, which is reckoned the central region of the whole of Gaul. Hither all, who have disputes, assemble from every part, and submit to their decrees and determinations. This institution is supposed to have been devised in Britain, and to have been brought over from it into Gaul; and now those who desire to gain a more accurate knowledge of that system generally proceed thither for the purpose of studying it.” —Bellico Gallico. 6.13

The Druids are also (by others) described as philosophers, doctors of medicine, and literate in Greek. Both the Celts and the Romans demonstrate a very complex priestly class, but all Indo-European groups had a prestigious priestly class heavily engaged in liturgical elements of their religions. The Indians their Brahmins, the Iranians their Magi, the Slavs their Zhrets, all with varying degrees of inter-tribal coordination depending on the time period. All, except for one.

The Germanic Tribes had various people associated with magical abilities or religious prestige, but lacked the crystallized priestly caste that is characteristic of basically every other Indo-European society. When exactly this occurred is not clear. Was it always a trait of the Germanic people? This could put the date of this “schism” even earlier than the religious schism which likely occurred between the Indo-Aryan and Iranic peoples.

I think a more likely series of events has to do with the Germanic religious fascination over the Runes, an esoteric writing system reserved only for the Warrior Aristocracy. I strongly recommend watching this video from Survive the Jive on Runes, particularly from 15:02 onwards.

Firstly, Runes are clearly a heavily manipulated writing system. It is not just an adoption of Etruscan or Rhaetic or Latin. It was reorganized by the Germanic elite using these earlier letters. Runes are viewed as having magical and esoteric qualities, with the word Rune meaning something more like “secret”. The Runic esoteric study may have evolved from a previous bardic or mantric tradition, which would later be divided into the Norse tradition of Galdr. A Finnish cognate for Rune means something along the lines of “sacred song”, and Finnish has a reputation for being an “ice box” of early Indo-European words, so it is possible this was the initial meaning.

Masters of Runes were known as Erilaz, which really just means Earl. Again, demonstrating that these were just Aristocrats who had intensely studied the Runes, they were not priests. Sacrificial ritual, while common in Germanic society (Blót), was not initiated by a crystallized religious elite. It was initiated by the warrior elite, or men of high standing in the community. In both these cases, Germanic religious life is characterized by a personal enthusiasm towards the study of religious secrets, and a collective ritual life without a strong hierarchy other than a preference for the social and military elite to lead ceremonies and sacrifices.

Meanwhile, what traits characterize Protestantism? A focus on Bible Study over Liturgy, and a belief in “universal priesthood” where there isn’t really a divinely ordained set of priests. Even the layout of Protestant Churches suggests a movement away from liturgy and towards Bible study, with the most extreme low-church Prots basically attending Church as a book club meeting for only one book that they read over and over again. Is it really any coincidence that Runologists in the post-conversion world, like Guido Von List and Johannes Bureus, were also interested in Kabbalah? Well, I don’t want people to take away from this some sort of connection between Judaism and Germanic Paganism. They’re just as different from each other as Judaism is from every other Pagan tradition. But certain elements behind Germanic Paganism might explain why the Germanic peoples accepted a more doctrinal Judaization of their religion (again — see the article I linked above before commenting anything about that. I don’t mean it in an inflammatory way)

If Germanic Paganism did actually sustain a deep influence hundreds of years after it died, then I would be willing to believe that the differences between Germanic Paganism and other Indo-European forms of Paganism contributed to the Germanic embrace of Protestantism. However, I am not entirely convinced by the evidence. Yes, it’s a nice correlation, but many other factors have to be accounted for. It would be good to see a more in-depth study comparing the success of Lutheranism and Calvinism to the location of Pagan sites. It is clearly a small effect anyways, compared to other factors, but it’s an interesting angle to approach Protestantism from.

Even before the Protestant Reformation, the Germans always had a bit of an issue with Church authority over religious manners. To the Germans, it made more sense for the Roman Emperor and his aristocrats to choose clergy. This resulted in the Investiture Conflict. The Humiliation of Canossa and Concordat of Worms left the German lords defeated by the Church, but Frederick I and II Hohenstaufen would famously try and return the religious authority to the Aristocracy. When the Protestant Reformation rolled around, the Holy Roman Emperor ended up siding with the Papacy, but large amounts of German princes opted for Lutheranism as a way to escape clerical brow-beating. Even for the Habsburgs, their decision to stay in The Church had to do with their increasing leverage over the Church during the reformation. After Charles V’s own Landsknechts insubordinately sacked Rome in 1527, the Pope had effectively lost the power struggle between The Catholic Church and the HRE. Clement VII had basically become a puppet for Charles V, which is what people don’t recognize about Henry VIII’s decision to split with the Church. Due to the unique refusal to accept his annulment, it was clear that the Church had become the political instrument of another secular ruler, and so decided to do the same thing in order to counteract the Habsburgs.

Also, there is a good substack article somewhere on this website suggesting the possibility that the Habsburgs basically had some or Henry VIII’s people around him, relatives, and child(ren?) killed. Unfortunately, I have lost it! I wish I could find it again, so if any of you know what I’m talking about, help me out!

https://x.com/rawbloodenjoyer/status/1784451729331032186?s=46&t=YFeGPiZL3mos8Dqb1Hnvxw here’s a thread that talks about what you mention at the end

You can explain the south of Germany being more catholic because they are more alpinoid celtic mutts with superstition in their dna. Nordics are the complete opposite, Nietzsche talks about this in BGE.