The Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation

The Renaissance as a rebirth of late Hellenism, and the Protestant Reformation as a Judaizing movement

If you didn’t see, I wrote a post asking whether or not I should write about the Renaissance or the age of consent. So far I’ve been advised only to write about the Renaissance. The age of consent business really has to be talked about at some point, but for now I’ll avoid it. I wanted to write about the Renaissance after writing a few comments about it on iFunny, and I think I’ve written about it before, but in my opinion the Renaissance was nothing if not the rebirth of Pagan principles. I’m also going to be writing about Protestantism, which ended the spirit of the renaissance both directly and indirectly through the counter-reformation constricting the ideological range of Catholic institutions. I’ll get to Protestantism later.

Anyways, the Renaissance has a somewhat ambiguous place on the dissident right. It exists in a state of limbo between the “traditional society” of the middle ages, and the bourgeois liberal enlightenment which many pin all of our problems on. So there is some pressure to view it as a negative. But, not many people do, because the Renaissance doesn’t share the sort of political or ideological novelty which defines later movements. After all, the term ‘renaissance’ literally means “rebirth” in French.

It is widely recognized as the rebirth of Greco-Roman artistic traditions, but people usually assume this is because of increasing artistic skill alone. This is partially true, the development of Linear Perspective explains some of the apparent increase in the realism of painters. When discussing the increase in realism during the renaissance, you come to the issue of to what degree these developments are a product of increase in artistic skill, and what is a change in values. Medievalists and OrthoDOGS will insist that the lack of realism in medieval artwork and Orthodox iconography was by choice. That there is something distastefully earthly about the sort of religious painting of Michelangelo or Raphael. I am somewhat skeptical of this, because linear perspective wasn’t just lacking in medieval Europe. It is barely used in human history before the renaissance. There are a few examples of its use earlier on, but from my understanding Brunelleschi was the first to generalize the method of linear perspective. Before Brunelleschi, anyone looking to use linear perspective would have had to estimate perspective. Also, medievalists and EOs both have a vested interest in downplaying the artistic genius of the Renaissance, which was a Catholic and Western phenomenon. Most medievalists are, by the way, total shitlibs. I have my theories why, but don’t want to diverge too far off the conversation.

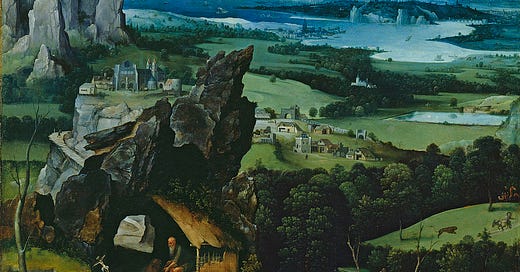

All that being said, worldview certainly played a role. Advancement in realistic visual arts was slow compared to advancement in other fields, mainly architecture, throughout the middle ages. The main focus of visual arts became either the human form, or the landscape. Maybe I am just naive to medieval art, but I don’t know of any influential landscape-focused scenes from between the 5th and 14th century in Europe. But by the 15th century they start becoming very common.

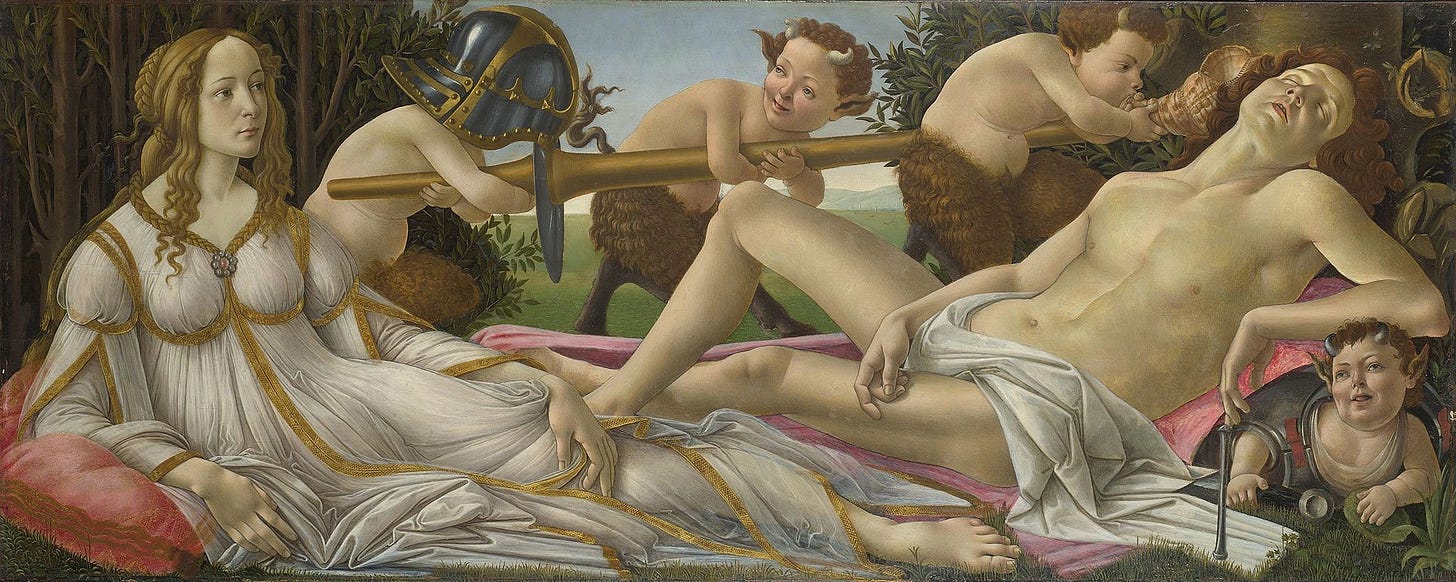

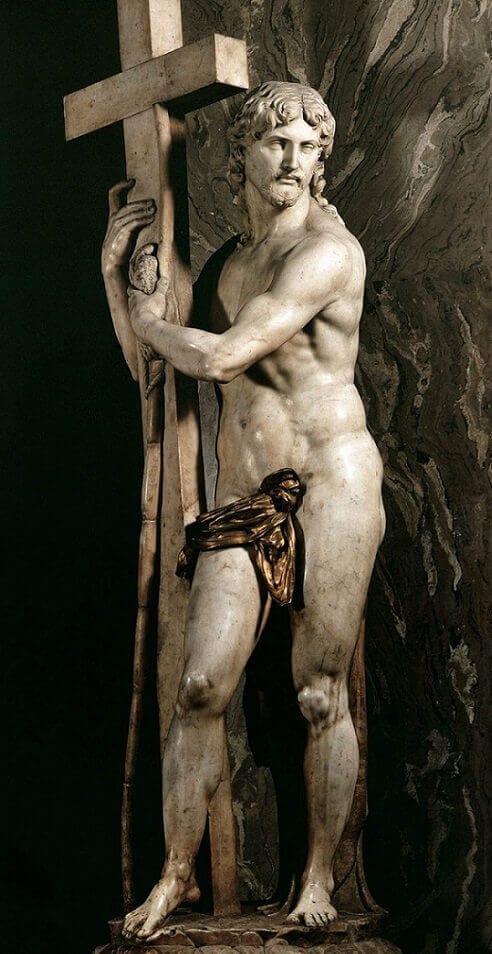

This general trend is known as ‘Renaissance Humanism’, which is not to be confused with Secular Humanism. They are completely different things. Renaissance Humanists believed that the perfection of nature and subsequently the human form made it worthy of artistic focus, which did not directly focus on something wholly divine but was indirectly focusing on the divine, because God is the source of beauty. While this concept is, in a more dialectical way, completely compatible with Christianity, it is clearly a product of the growing Platonic influence on Italian thought during the late middle ages. You can see it clearly in art. Notice, by the way, that this is not secular. It is completely intertwined with religiosity. Michelangelo gives the risen Christ the body of the Greek athletic ideal because he associates this physical perfection with divinity. He does similar in giving David the body of the Kouros. Already by the high medieval period, Aristotle had been brought to a position of prominence within the Church, but Plato had gone out of style. Early Renaissance writers like Dante are already filling biblical unknowns with understandings derived from Aristotelian physics and Platonic cosmology. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Italian philosophers (many of which were clergy) gravitate towards Perennialism, the belief that religious traditions throughout time and space point to a single “perennial” truth — mainly citing examples from Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, Christianity, and Judeo-Islamic mysticism. Nicholas of Cusa, Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, Giordano Bruno, Pletho, Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus, Johannes Trithemius, and Conrad Celtes are some examples of this on the intellectual front. They were not seeking necessarily to replace Christianity (except perhaps Pletho), but their qualification of pre-Christian traditions and their sympathy for pantheism motivated the Humanistic drive and the return to the artistic tradition of antiquity. In Platonic thought the divinity of nature is not just dialectically or poetically true but ontologically true, because God ultimately comprises nature and natural order is governed by divine forms. And yes, the great artists of the renaissance were likely influenced not just indirectly by these figures. Some of them are even found on Raphael’s School of Athens. They wanted to complete Christianity on the a priori level, to rationalize it within an overarching syncretic Platonic system. Ultimately, this effort failed. It is possible it could have never succeeded. In my opinion, it misunderstands the Christian faith on a deeper level. But, it declined in particular due to the Protestant Reformation, which in my opinion was a Judaizing movement.

This is not to shit on the Protestant Reformation. I don’t really prefer Catholicism or Protestantism, but from an outsider’s point of view Protestantism is clearly more similar to Judaism in a lot of ways. The focus on personal bible study over liturgy, the disdain for extravagance and idols in religious spaces, the rejection of Maccabees as canonical, the allowance of clergy to have families, and the emphasis on revealed scripture and faith over deduced theology and philosophy. Protestants also seem, in my personal experience, to spend a lot more time on the Old Testament. I don’t really know why this is the case. Luther calling the Catholic clergy akin to Pharisees and disliking Jews isn’t an argument against Luther being a Judaizer. I’m not saying he was a Jew. He wasn’t, but he sought to skim off much of the supplementary teachings that the church had developed. Luther very clearly did not believe in “virtuous pagans” as he apparently gets angry over fellow reformist Ulrich Zwingli at the Marburg Colloquy suggesting that Plato and Aristotle can sort out their issues when they go to heaven. Saying:

“Doctor Zwingli, they were pagans; they were not baptized; they are roasting in the everlasting fires of Hell. [Zwingli: “But they were good men, were virtuous and followed their consciences.”] If you talk like this, you're not a Christian—and I regret to have wasted my time with you.”

Luther is also critical of the Scholastics and their emphasis on logicizing and rationalizing Christian theology on an Aristotelian basis, although he isn’t necessarily criticizing Aristotelianism itself. This criticism was also going around in Judaism at the time, although frankly I would say Judaism has always been more focused on scipture-devotion than Christianity. I wrote about the uniqueness of the Christian trinity on iFunny a while back and how it changed Christianity, and it was pretty popular, so maybe one day I’ll take a crack at recreating it on the ‘stack.

You can see the similarities in architectural taste too. Synagogue interiors (at least before assimilation) are rather plain. Not all Protestant churches are plain, I think by the late Baroque you start seeing some rather sophisticated Lutheran churches, but Calvinists in the Netherlands went through a period of iconoclasm and basically painting over or destroying the glitz and glamour of the region’s large churches.

Another paganizing force of the renaissance was the increasingly political and militaristic role of the Church. Well, in some sense it is Pagan. Maybe this is a product of my own Pagan perspective, but the ecclesiastical authority of the Roman Emperor always gave me the impression that it was a Christianization of the Imperial Cult and the Emperor’s role as Pontifex Maximus. Constantine didn’t actually ever retire the title of Pontifex Maximus, it was only retired under Gratian’s rule. It’s no wonder that Pagans and the Traditionalist crowd a la Evola have always had a soft spot for the Ghibellines, because in this context the Ghibellines represent the organizational element of the Church descended from the old Roman religious strata (and because it represents the political primacy of the warrior class over the priestly class, which Evolaites support, but Dumezilian stuff deserves another post).

Anyways, I’ve always found it a bit hair-splitting because the late medieval Papacy was already becoming more akin to a sort of divinely ordained warlord and king rather than just a religious leader.

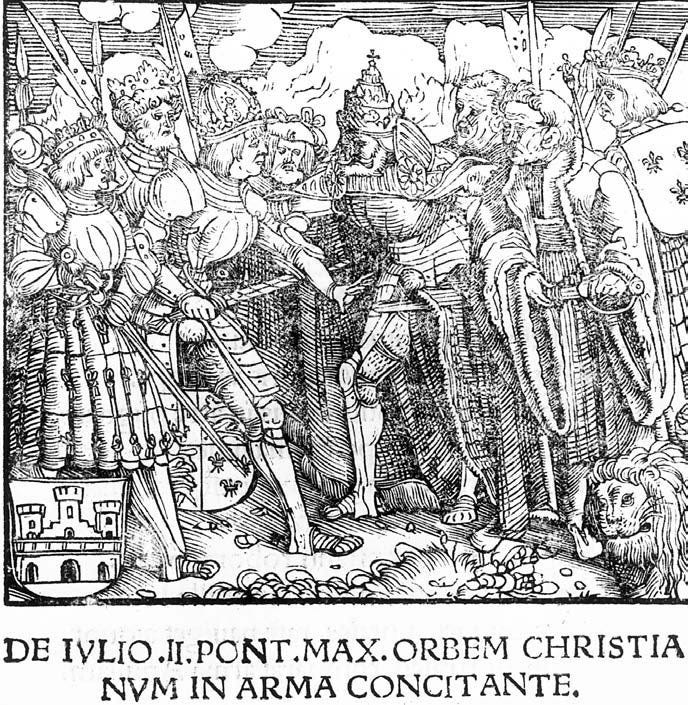

Now, the example most significant to the Protestant Reformation is that of Julius II. Named not after Julius I, but after Julius Caesar. The regency of Julius II was very controversial and his time as pope was attacked harshly by the new Protestant schismatics, as he represented the shift of the Papacy from a clerical position to that of a de facto political leader. It is hard to deny Julius II’s desire to appear as the successor to the Roman Emperor. He occupied himself with war, driving the Germans, French, and Spanish (i.e. Borgias) out of Italy, who he considered all Barbarians. When not busy with this he was commissioning a sizeable portion of the entire Italian High Renaissance. Pick any famous work by Michelangelo or Raphael, and there’s a good chance it was commissioned by Julius II. Julius’s aesthetic emphasis on pre-Christian motifs is lumped in with Julius’s larger attempts at renovatio urbis, or “renewal of the city [of Rome]”, not just by returning Rome to its ancient grandeur but by connecting the Christian papacy to the offices of antiquity, even going so far as to incorporate religious motifs from antiquity into Christian holy spaces. From the journal article Gods in the Garden: Visions of the Pagan Other in the Rome of Julius II by Marco Piana:

In line with this logic, the official incursion of pagan antiquarian aesthetics and thought within the Holy See during Julius’ pontificate can be seen as one of his most relevant proclamations of his theological approach to Christianity. In the pope’s view of the Cortile del Belvedere—and of his renovatio urbis as a whole—the pagan gods of antiquity were allowed to share the sacred space of the Vatican with the holy symbols of Christianity, exactly as the pagan philosophers were permitted to face the Church Fathers in the frescoes in the pope’s private library and office, the Stanza della Segnatura.

According to many of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century testimonies on the Belvedere garden, several humanists and poets were inspired by the impressive sculpture collection found in Julius’ garden. Since its discovery in the early months of 1506 and subsequent placement in the garden, for example, the statue of the Laocoon saw an immediate and long lasting fame in the world of letters, testified by humanists such as the Florentine Giovanni Cavalcanti (1444–1509) and the Venetian Pietro Bembo (1470–1547). Moreover, Evangelista Maddaleni de’ Capodiferro and Baldassarre Castiglione’s poems on the garden sculpture once known as the Cleopatra, and Bembo’s letters to Filippo Beroaldo il Giovane (1472–1518) and Gianfrancesco Pico’s associate Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto (1477–1547) on their poetic compositions seem to indicate the presence of a florid new trend of lyrical works dedicated to the Belvedere statues, conceived to celebrate the glory of Julius’ pontificate. These poems, likely devised in order to please the pontiff, very often saw the statues of his garden as the protagonists of a new encomiastic mythology in which the greatness of Julius’ pontificate is celebrated in terms that go beyond the Christian paradigm. (pp. 293-94)

In a letter to Isabella d’Este (1474–1539) dated 20 February 1513, the Ferrarese envoy Battista Stabellini described the latest Carnival in Rome as a triumph dedicated to Julius II, with a series of chariots carrying, respectively, an Egyptian obelisk, an angel slaying a hydra, and a temple of Apollo, with a replica of the Apollo Belvedere shooting arrows to represent victory. This parade, the last Carnival parade under Julius II, can easily be seen as a synopsis of the pontiff’s view on religion that was an original mixture of Hermetic mysticism, Christian symbols, and Olympian triumphs. Another reason why the poem Ibidem Apollo Loquitur is especially important is that it explored the relationship between Julius and the sun god in a rather unorthodox approach. In the poem, in fact, the statue of the Apollo Belvedere animated itself and revealed himself to the pope as the sun god in person. After appearing in all his might, the pagan deity spoke to the pope and revealed his origin and his mission on Earth:

It is I, Apollo, the eternal guardian of Julius and the gens Iulia, who delivered you, unvanquished one, from so many perils and with my nod carried you above the aether. Do not gaze at me in marble form now, behold the real me, the way I appear in the lofty and heavenly Olympus. Here I entrusted you, o venerable one, with all the souls of the Romans, with city walls reaching to the heavens, and with supreme powers of divine majesty. Not for nothing you are the greatest undertaking of the Gods: through you emanate laws and gifts of peace, and you watch over the city of Rome, and the World. You survey all with a wise intellect, nor does unbridled desire for riches press upon you. You desire to help, not to harm. Through you, through you the souls return to me, and Rome rises itself once again. (pp. 295-96)

Martin Luther’s visit to Julian Rome in 1510 left him repulsed. Albeit, the Pope’s bombastic attitude and pagan stylistic choices were not his top concerns, but he does list them as grievances and views them as part of the general insincerity of the Church.

Anyways, if this is what happened during the renaissance — i.e. a revival of pagan ideas and aesthetics, whatever happened to the Renaissance and its philosophy? Did it evolve into Libtardism? Well, I don’t think so. First of all, one of the measures of the Counter-Reformation was a movement away from Renaissance Humanism, in order to save face. The Roman Inquisition purged many of these elements from the Italian intelligentsia. The vacuum left in by Renaissance Humanism in European intellectual circles was filled by what we might recognize as “modern philosophy” — the Rationalists and the Empiricists.

Descartes, Bacon, Leibniz, Spinoza, Locke, Hobbes, Pascal, you know… All of those guys… Yes, maybe Spinoza and Leibniz have some beliefs in common with Plato, but they’re clearly their own animals altogether and not a product of the process which was going on during the Renaissance. It’s possible that the massive cultural output of the Renaissance resulted in the scientific environment which would lead to the Empiricist-Rationalist dichotomy, but — and I’m really no expert — they don’t seem to be directly connected. Just looking at the names alone should tell you this. These guys are from the UK, France, and the Netherlands, with one German — and this is 17th century Germany. Very different from the Germany of the Renaissance. Meanwhile, our Renaissance names are mostly Italian, secondarily German, and one Greek.

The transformation of Art was much more straightfoward. The Catholic Church bankrolled the Baroque movement, which might look similar to the Renaissance on the surface but is in many ways a bending-forwards of what the Renaissance was doing. Art becomes much more dramatic and dynamic, starting with the transition to mannerism and continuing further throughout the Baroque period. The art of the early Renaissance impresses order upon the viewer — the vanishing point, the objective perspective, the ideal city, man, and nature. In it there is a sort of Platonic perfection which is strived for. You see this in architecture as well. Renaissance architecture is heavy, it’s geometric, it’s ordered and based on mathematical harmony. Baroque architecture is distorted, it is filled with methods of illusion, it messes with perspective. The purpose of Baroque art and architecture is to break reality, it is meant to give the feeling of an ecstatic state. It is meant to convey the miraculous and mysterious nature of God coming into the world.

Versus:

Versus:

P.S. I’m not trying to shit on Protestantism or Baroque. I like Baroque and Renaissance equally.

Astute observation. The history of Christianity as the peoples who became Christians seems to be:

Jews/Hebrews . Hellenes . Romans . Germans and Franks . Others.

So to reject Catholicism and go back the the Jews/Hebrews root is Protestantism, IMO.